Image Source: Pixabay via Pexels

The goal of any enterprise is to deliver superior sustainable performance. For a business, “performance”, means return on investment; “sustainable” means over the long term rather than to meet the next quarterly earnings targets; “superior” means better than competitors so that the firm is always first in line when it needs more capital – this makes it more sustainable. What does it take for an enterprise to deliver superior, sustainable, performance? First, it takes good strategy, the integration of choices on where and how to compete. Second, it takes good execution, the integration of actions to deliver the strategy. Both of these require good leadership to ensure that the right choices are made and the right actions are taken. In this special feature by Dr. John Wells, President of IMD, Switzerland, the focus lies on winning strategies and the realities of competition, competitive advantage and profits.

Intrinsic Potential for Profits

Evaluation of any business opportunity begins with identifying the value created for the customer. This is a measure of the maximum price a customer is prepared to pay. We need to compare this with the cost to supply the customer. The difference is a measure of the profit potential.

However, customers seldom pay the highest price. The actual price is a function of the level of competition in the marketplace. If the competition is low, prices approach the maximum the customer is willing to pay. If the competition is high, then prices can quickly fall to the cost of supply or even lower, in which case the firm is likely to go bankrupt. The level of competition varies significantly from one business to the next and drives the level of profitability that an average player can expect to make.

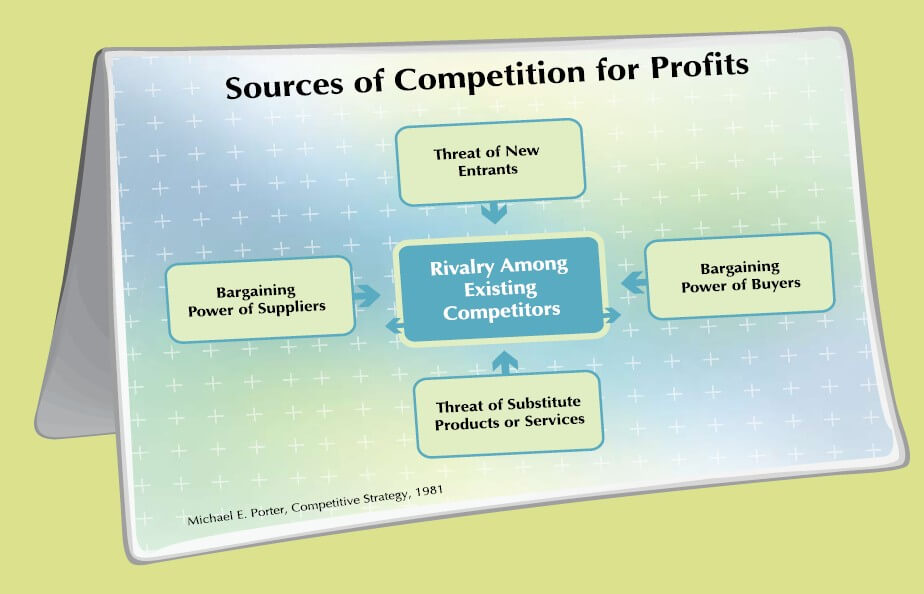

Sources of Competition for Profits

When assessing the level of competition in a business, it is easy to make the mistake of focusing only on direct rivals. Of course, the number of direct competitors is important; the bigger the number and the tougher they fight, the lower the average profits. However, it is important to take a broader view of competition. There are many sources of competition for profits [see Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy and chart 17]. Powerful customers can extract most of the profit from a business, as many companies have discovered when they serve large retailers like Wal-Mart. Powerful suppliers can also extract much of the profit; for instance, the personal computer industry is not very profitable because most of the profits in the supply pipeline are captured by Intel and Microsoft.

However, even if there are few rivals and supplies and customers are weak, profits will still not last very long if it is easy to get into the business. To achieve good profitability in the long term, barriers to entry must be high. Entrepreneurs often fail to take this into account. A new idea may look incredibly valuable but it will not be profitable for long if it’s easy to copy; when getting into in such a business, it is important for a firm to build up barriers behind it.

Last but not least, substitute products put an upper limit on the price a customer will pay and therefore the profits a firm can make.

Careful assessment of the five forces indicates the level of profitability an average firm can expect. It also indicates ways in which the firm can position itself to achieve above average returns e.g. by choosing to serve less powerful customer segments. Trends in the five forces also provide an indicator of whether average industry profitability is going to rise or fall. Smart investors look to invest in industries where profits are likely to increase in future and buy into them at a discount. Equally, they look to sell out of businesses at a premium where they think profits will decline in the long-term.

When evaluating a business, it is also useful to take a broader view of the total value system, looking upstream at the supply chain and downstream at the distribution channels. It is equally useful to look sideways at complimentary products. The objective is to identify where in the value system profits are currently made and how this will change in future. For instance, 25 years ago most of the profits in the music business were made by the major record companies. 10 years ago, much of the profit was being extracted by large discount retailers. Now, digital distribution is destroying the retailers and putting even more pressure on the record labels.

Strategy is therefore about choice and the first big choice a firm must make is which battlefield to fight on. Some are much more attractive than others. So which businesses are more attractive? Which segments within the business will deliver above average returns? Is upstream or downstream more attractive? How is this likely to change over time? And how can the firm take advantage of this knowledge to position itself to achieve above average returns?

The Search for Competitive Advantage

While a firm may be able to find an attractive segment within an industry, it is likely that others will find it too. The issue now becomes one of building competitive advantage to help the firm to win. One approach is to provide greater value for customers so that the firm can charge higher prices – a differentiation strategy. A clear alternative is to achieve lower costs than competitors to improve profit margins. It is often difficult to focus on doing both at the same time, and herein lays the second major strategic choice a firm must make. What weapons do they choose to win? Are they playing a differentiation game or a lower-cost game?

The profit potential for a business is therefore made up of three components; intrinsic average profitability of the industry; the incremental profit from finding attractive segments within the industry; and the size of competitive advantage compared to others who are competing in the same segment.

Differentiation – Driving Higher Price Realization

Differentiation is not merely about being different or unique. I know of many companies with unique product offerings that are unprofitable. The goal is to be better, better as defined by the customer. The acid test of whether a firm has better products is that they will support a price premium while holding market share. If a firm is charging the same price, then it should be gaining share because customers should clearly prefer them. However, just because a product supports a price premium does not mean that it has a competitive advantage. The definition of advantage is that it translates into higher profits; therefore, the price premium must exceed any extra costs involved. Many firms make that mistake of adding two dollars to the cost of their product to make it better but only achieve a one dollar price premium. This is a sophisticated form of charity. Differentiation requires strict economic discipline. The firm must know what its unit costs are relative to its competitors and its relative price realization. It must only add to its cost base where it knows it can achieve a price premium that will cover the extra costs involved.

To achieve a price premium, it is very important to have deep knowledge of customer needs. For instance, in the bearing industry, customers are prepared to pay more than double for a set of bearings that last twice as long because they not only have to buy half as many bearings, they also save on fitting costs. Understanding customer economics provides insight into what price premium the market will bear. A disciplined approach to differentiation requires firm estimates of willingness to pay.

Scope of Activities to Capture Value

When a firm identifies how to create extra value, it must make a choice as to how it will capture that value. What activities should it invest in? For instance, in the case of the bearing manufacturer with bearings that last twice as long, one option is clearly to sell the bearings, but it may make more sense to offer a machine maintenance service because this allows the firm to capture more of the savings in fitting costs. The firm might also choose to start a franchise offering machine maintenance services. It could also license other bearing producers to make the bearings. There are many approaches to competing, with different investment profiles, different potential for capturing the value and different levels of strategic control. Strategy is choice!

Lower Cost

To achieve high levels of profitability, low cost is not good enough; the goal is to be lower cost than the competition. Moreover it is not good enough to be lower-cost but offer an inferior product. The goal must be lower cost for the same product or service. If customers demand a discount, then this must be smaller than the cost advantage to deliver superior profitability.

Whether a firm chooses to be lower-cost or differentiated, it is clear that it must have a very good idea of its relative cost position. It is difficult to obtain such information from published accounts. It is better for the firm to look at the cost of every activity they engage in and to build a model of how each of these costs behaves (e.g. with size of operations, type of technology, location of plant, etc). With this understanding of cost behavior, the firm should then ask the question “what would our costs be if we were to operate exactly where and how our competitors are operating”. This provides a reasonable estimate of relative cost position and also helps to identify how activities must be adjusted to build a cost advantage.

Scope of Activities to Lower Cost

Once the firm has identified how it can achieve lower-cost, it must choose the scope of its activities. It may choose to avoid activities where there are plenty of low-cost suppliers and a lot of competition; it makes more sense to buy such products or services in the marketplace. On the other hand, activities that are critical to competitive advantage or very profitable are higher priorities for investment.

Anticipating Competitors

There is no such thing as a strategy in isolation. It all depends upon where competitors are positioned and what they are likely to do. What advantages do they have? What is their primary goal? How have they acted in the past? What does this tell us about how they are likely to act in future? How they are likely to react to any moves that the firm might make? Such insights allow the firm to anticipate moves and counter moves and decide on its actions.

A firm must assess how quickly a competitor is likely to react to anything they do, what it will cost them to react and what the move does for the firm’s competitive advantage. Ideally, a firm should be looking to make moves where the competitor is likely to be slow to respond, where the cost of response is very high, and where, as a result of the move, the firm has improved its relative position.

When a competitor delays reacting because of the costs involved, it allows the firm plenty of time to enjoy the extra profits from their new idea. However, as long as the move puts the competitor at a disadvantage once they have reacted, a firm should still see any such move as strategically desirable even if the competitor reacts fast. The challenge is when the competitor becomes more competitive once they have reacted. In this instance, as long as the competitor reacts slowly, it still makes sense for the firm to introduce the new idea as long as they can make good money before the competitor reacts. However, once the competitor copies, the firm has no choice other than to find another new idea in order to generate superior profits because the competitor has now become much stronger. This strategy is a matter of keeping ahead of the competition.

The most dangerous new idea is an idea that the competition will copy fast and which they can do at lower cost. Any firm that contemplates introducing such a product is committing strategic suicide.

Competitive Advantage – Faster and Smarter

Capital One is an example of a firm that has built its competitive advantage based on its ability to react faster than the competition. To sustain its market position, they developed an organization that was capable of generating and testing 50,000 new ideas a year – an innovation machine. It therefore obtains valuable proprietary information as a result of every one of those tests it performs. It is also playing a smarter game because it has superior information on where to seek out profits. Hence, there is more to competitive advantage than lower-cost and differentiation. Firms can also see to play a faster, smarter game.

Business Unit Strategy versus Corporate Strategy?

Most firms operate in several businesses. Corporate strategy typically concerns itself with deciding on the portfolio of businesses to invest in, and whether to try to extract synergies between these businesses. Business unit strategy is the integrated set of choices a firm makes to deliver secure and sustainable performance within a particular business.

When looking at the difference in profitability of multi-business firms, about 20% is explained by the average level of profitability of the industries the firm invested in. Another 30% is explained by the strength of the position of each business. Less than 5% appears to be the result of synergies. A full 45% appears to be the result of good execution. This is a useful guide as to where the firm should invest its efforts.

Not all firms follow this approach. Indeed some firms buy businesses in industries with low profit potential and with weak positions, and put them together in the hope that synergies will improve performance. This typically fails. The reality is that putting a group of dogs together does not add up to a racehorse, it adds up to a dogs’ home. When making strategic choices, focus investments on attractive industries and drive for strong competitive positions. And focus on great execution.

The Benefits of Corporate Strategy

If the synergy benefits of competing in multiple businesses are low, then it is worth asking why any firm should want to do it. Apart from synergy, there are three other major reasons: diversifying business risk; diversifying lifecycle risk; and building efficient internal markets for capital, executive talent, skills and information.

Diversifying Business Risk

Different businesses show fundamentally different cash flow profiles over the business cycle. For any individual business, cash generation can be very volatile, and there is a danger of bankruptcy at the bottom of the cycle. By buying a range of different businesses whose cash flow streams are not correlated, multiple volatile cash flow streams can be smoothed, providing steady returns to investors and reducing the probability of costly and unnecessary bankruptcy. It only takes investments in about eight industries to benefit from these effects.

Some strategists question why a firm should wish to invest in multiple businesses in this way. They argue that a firm is better off focusing on one business because shareholders can diversify for themselves so why should the firm diversify? This argument does not hold for family businesses because the managers are also the owners. Moreover, it is easy to see why any top management team would want to diversify such risk to preserve their jobs and provide steady incomes.

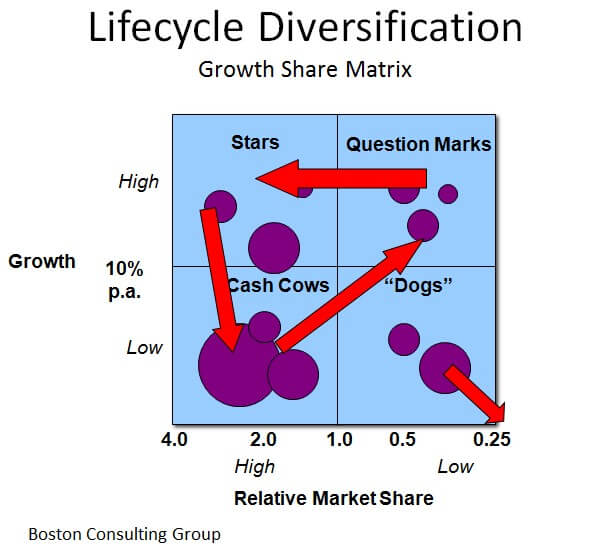

Diversifying Lifecycle Risk

Typically, businesses have very different cash flow profiles depending upon what stage of the life cycle they happen to be in. New markets are typically fast growth. There are typically many firms competing, each with a small market share. Not everyone is going to survive; indeed everyone is a question mark. (See chart 40: Source, Boston Consulting Group) To keep up with the growth, such businesses typically consume cash. However, if they have plenty of cash available, there is a lot of potential to grow market share and build a leading position, turning the question marks into stars. Firms with leading positions in fast growth markets tend to be cash neutral. As the growth slows, they begin to spin off a lot of cash because of their superior competitive position – they become cash cows. This strong cash flow can be used to “feed” question marks and develop new stars for the future. In this way, the firm can maintain a self-funding portfolio of businesses at different stages of the lifecycle.

The question remains as to what the firm should do if they find they have a weak market position in a growth business. It costs a great deal of money to build market share in a weak business in a slow growth market and the effort is seldom worthwhile. These businesses are dogs, which need to be divested or shut down.

Again, some strategists argue that there is no need to maintain an internal capital market because it is always possible to find outside investors if a firm has a good business idea. The current financial crisis should demonstrate why such a view is misguided. Capital markets often fail. Indeed, there are many strategically healthy businesses currently going bankrupt because their access to capital has suddenly disappeared. At such times, cash is king. My own view is that it is only easy to raise capital if you do not need it, so make sure you raise it when times are good.

Maintaining a balanced portfolio of businesses at different stages of the lifecycle makes sense for any enterprise; it makes particular sense for family businesses where there is no separation between manager and owner. Apart from the benefits of a self-funding portfolio, it also provides opportunities for the next generation to build business experience. They often wish to start a new business in a high-growth market rather than manage successful cash cows. Moreover, it is important that they demonstrate their leadership potential to themselves, the family and non-family members before they are asked to take charge.

One challenge for family businesses is that it is often difficult for them to divest dogs. They are frequently faced with the dilemma that business that was once the cornerstone of the family enterprise is now in a weak position and delivering poor results. However for reasons of respect, the family cannot face the decision to exit. Under such circumstances, the challenge is to identify a segment within the business where it is possible to achieve above-average returns. Although this may still mean the business is not a huge profit generator, it minimizes the losses while respecting the tradition that holds the family together.

Creating an Efficient Internal Market for Key Resources

Diversifying business risk and diversifying lifecycle risk are both examples of the advantages of creating an internal capital market. It is also possible to create an efficient internal market for other critical resources such as executive talent, skills and information. For instance, General Electric invests heavily in building a strong pool of executive talent. Indeed, it is probably one of the best business schools in the world. Rather than rely on headhunters to find good executives, General Electric looks to its internal market to find good candidates, and it has much better information on these executives than it would ever obtain from an outside recruiting process. It also relies on its internal cadre of a black belt six Sigma consultants to help improve its efficiency rather than hire outside consultants. In this way, it can keep its learning proprietary. It also relies on the sharing of internal information and expertise in many ways. It is difficult for firms to trust information from outsiders, but when it comes from an internal business unit, it is often more reliable.

For the internal markets within General Electric to work efficiently, the bonds of openness and trust that tie General Electric executives together must be strong. It is these same bonds in family business that create even greater potential to benefit from managing efficient internal markets.

Tharawat Magazine, Issue 4, 2009