In his book, Trapped in the Family Business, Dr Michael Klein explores the difficult situation that can occur when family business members feel they no longer fit in their role or the organisation as a whole. Informed by his experiences as a psychologist and family business consultant, the author elaborates a deeper understanding of this often damaging and counterproductive reality.

The situation may seem unimaginable. Working alongside family towards a common goal can be both fulfilling and lucrative. However, there are those who wish their familial obligations did not extend into a professional context.

In many cases, guilt prevents people from voicing their concerns in a healthy way, and in staying silent, they may also feel isolated and helpless. Complex family dynamics make the issue incredibly sensitive. Belonging, responsibility and fear of the unknown all play a part in exacerbating the problem.

There are techniques to make a positive change, however. In his book Dr Klein provides some practical guidance to this end – you’re not alone, and there are ways to remedy the situation.

Recently Tharawat Magazine had the opportunity to sit down with Dr Klein to discuss the book, what to do if this situation affects you or someone you know and the overarching importance of self-identity.

Dr Klein’s book can be purchased on his website or on Amazon.

Why such a provocative title, Trapped in the Family Business, and what motivated you to write this book?

I can answer both these questions with one story. My first client as a business consultant bought out his father’s manufacturing company with his brother. From very early on, he knew this was not the best path for him but was interested in trying to make it work.

After a series of conversations, I learned he had been an art history major and never had much of an interest in business – he was only planning to do it for three to five years. However, because the firm had been so successful, they both ended up staying far longer than they had initially planned.

Unfortunately, he could not bring himself to broach the subject with his brother. As a result, they spent a lot of time at each other’s throats.

It struck me that there weren’t resources available for people who discover that working in a family business is not the best fit for them. I wrote the book to say to others like him, ‘Hey, you’re not alone in this. It can be understood, and you can take a step back and think about what your options are rationally and thoughtfully.’

In the course of your research, what have you found are the roadblocks that prevent people from initiating this conversation?

In my research for the book, in having conversations with over 30 people including those who worked in or had left family businesses, advisers and academics, several factors came up. Most frequently, it’s the combination of guilt and obligation holding them back from starting these discussions. A common refrain is, ‘Well, my parents provided this wonderful opportunity for me, and I can earn an income that I may not be earning otherwise.’ So, to even question their role feels like a betrayal. I’ve met many people who feel like they didn’t have a choice – this is what their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents all did. In these situations, joining the family business is expected, and there is no chance to question, ‘Who am I?’ or ‘What do I really want to do?’

I’ve heard from others who are in the family business to protect their ageing parents. One person I spoke to for the book came back to the family business in his late 30s because he saw his parents being taken advantage of by employees and vendors. All of those deeply ingrained family dynamics end up not only trapping people but making the very thought of opening up this Pandora’s box unbearable.

I’m sure people are reading this right now with an introspective frame of reference. What are the telltale signs that you might be trapped in your family business?

While not necessarily the primary cause, I’ve certainly seen a fair amount of substance abuse among those feeling trapped. Often that serves to numb people who are feeling frustrated, feeling like they’re not contributing, and deaden the discomfort that comes from conflict with family members. The data shows that substance abuse is more common in family businesses because it is easier to have it slip by. I worked with a client who would see one of the owners disappear for days on end because of a problem with alcohol. Because he owned the business, he could continue without any repercussions despite having a problem.

Disengagement is also symptomatic. Not feeling connected to the growth of the company, the success of the company or the mission of the company is a sign that presents. I’ll add that people who feel trapped tend to become more isolated from the people around them. If you see family members disengaging, and being less active in meetings, there’s probably some kind of problem, and something needs to be addressed.

Would having a family council in place make it easier to detect these situations?

Absolutely. Having a family council with ongoing family meetings is crucial. Also, engaging human resource professionals who can proritise the career development and professional trajectory of family members is often effective. It’s convenient to avoid these discussions so setting up a structure in which an HR person is trained and focused on family members provides safe places where these discussions can take place. You can prevent the situation from getting out of control if you’ve got people focused on the ongoing assessment of where family members fit in the business.

In your book, you outline three specific actions people can take if they feel trapped. Can you describe them to us?

The three successful paths to remedy the situation are: changing your perspective, taking action or ultimately exiting. Changing perspective often has to do with getting to know what it would mean to work in a non-family business. It’s almost a way of saying, ‘Look, we all know the grass is always greener on the other side, and we all have frustrations at work no matter where we are.’ I’ve worked with many people who started talking to recruiters, and once they got a sense of what it was like on the other side, realised what a fantastic opportunity working in a family business is. The thought exercise of removing yourself from the family business and thinking about what you have can make a huge difference.

<p>In terms of taking action, I’ve coached people in a few different ways. Sometimes, it can mean finding the elements of the job that give you the most satisfaction and steering more of your time towards them. Changing your role is another way to take action. Is there a platform within the company where you can rotate through different roles? If you haven’t come from the bottom up, then maybe it’s a great opportunity to see what other options there are and spend six months or a year doing that.

The last resort is leaving the business entirely. This prospect can be fraught with emotion because many people don’t have any work experience outside the family business. I’m working with somebody now who has spent 15 years in the family business and who is lacking in professional development. The outlook for the family business isn’t great, and so this person is only now starting to branch out.

All of these decisions require considerable thought and preplanning. I encourage people to involve an objective outsider who has no vested interest in them staying in the business. People need an advisor to help them answer the pertinent questions, is this a matter of changing perspective? Is this a matter of changing things inside? Or is this ultimately a matter of me starting to see what else is out there?

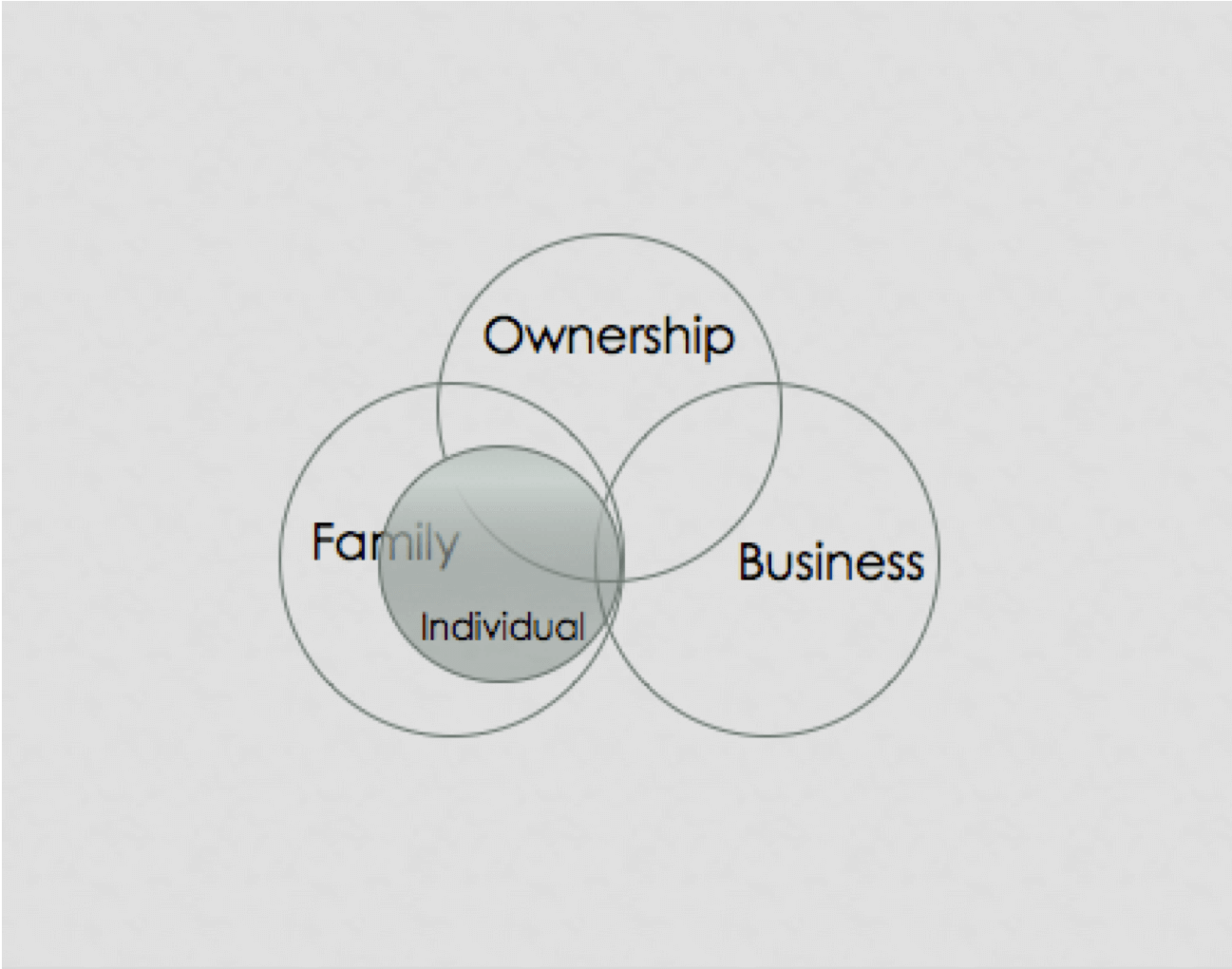

In family business, we often hear people talk about the three circles of family business engagement which are: ownership, management or employee, and family. In your book, you talk about a fourth circle. What is it and where did it come from?

The fourth circle that I added is for the self. For a lot of people whose whole lives have been spent immersed in the family business, the family business is all they’ve ever known. So, defining themselves separately from the family, from working in the business and from ownership is an extraordinarily complex process. It’s important to remember, as a fully functional adult you have the right to determine who you want to be. What are your key personality traits? What are your motivators? What are your values? What are all those things make you uniquely you?

I often talk to clients about creating a figurative moat around themselves and who they are as an individual. I’m working with somebody now who has a wife and two small children. I frequently encourage him to imagine a moat around him, his spouse and his children to create a space that is separate from parents and separate from the business. He has not yet had the opportunity to think about who he wants to be separate from them.

Now that you’ve completed the second edition of this book, what does the future have in store for you?

I’ve started conducting interviews about the flipside of being trapped in the family business, with the working title of Thriving in a Family Business. That book will touch on questions like, how as a parent or owner can you make sure that the people you bring are going to work towards the success of your company as a whole? How do you avoid all the pitfalls that so many family businesses fall prey to?

I want to explore how the right decisions are made so that people can feel fulfilled, connected, engaged, and satisfied within their family business. Thriving in the Family Business is going to be about drawing a roadmap, so owners and parents don’t inadvertently trap or burden the next-gen with responsibilities that are not a good fit for them and ultimately, not a good fit for the family.