It is common wisdom that small and medium enterprises are an important driver of growth, development and diversification for countries in all stages of development. Despite the GCC region’s strong entrepreneurial traditions and the large size of the Gulf SME sectors, however, there is still a great potential of sustainable diversification and job creation to be fulfilled. Dr. Steffen Hertog, lecturer at the London School of Economics and academic director of the International Institute for Family Enterprises elaborates on challenges and trends in GCC SMEs.

A major study I have conducted from 2008-2010 in cooperation with the European Chambers of Commerce, the German Chamber of Commerce in the UAE and the Federation of GCC Chambers shows that Gulf SMEs often focus on low-margin activities and employ an even higher share of expatriate labour than other private companies. To overcome the current limitations of the sector, state support policies as well as companies’ approaches to human resources and corporate governance may need to be rethought.

Gulf SME: what we know and what we don’t

Data on SMEs in the GCC are often limited to their total number, sectoral distribution and aggregate contribution to employment. Information contained in SME surveys in OECD countries, such as profitability, survival rate, or turnover, are generally not yet available in the Gulf.

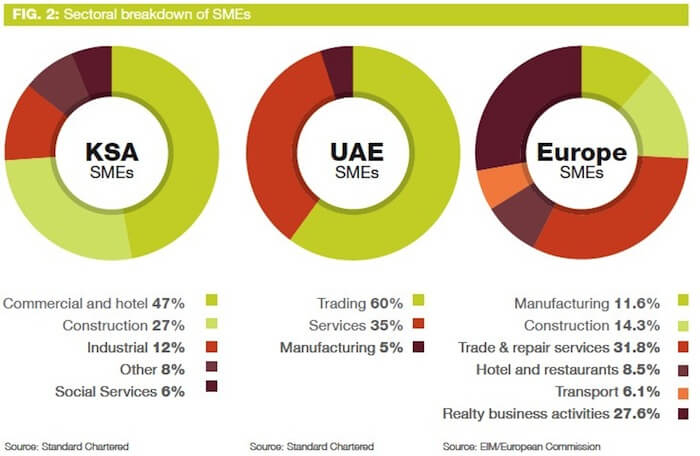

Yet, the broad outlines of the Gulf SME sectors are clear: SMEs constitute at least 90% of all businesses in every country of the region. A large share of SMEs is active in the trade sector; other important sectors include small-scale workshops, hotels and restaurants as well as contracting. They are less important in industry and other capital-intensive sectors.

Gulf SMEs tend towards lower-margin, small-scale service activities. The distribution across sectors in mature markets is more even and diversified.

Companies with up to 100 employees employ between 40 and 63% of the formal private labour force in different GCC countries, which compares to about 60% in the EU. In the GCC cases where we can distinguish micro, small and medium enterprises, it is clear that despite their numerical dominance, the contribution of micro-enterprises with up to 10 employees to formal employment is rather modest, providing between 10 and 30% of total formal employment in different GCC countries. European micro-enterprises by comparison account for almost one third of all private sector jobs across the continent.

The GCC track record is particularly weak when it comes to employment of nationals: 98% of SME employees in Saudi Arabia are estimated to be foreigners, while the share of foreigners in the Saudi private sector at large is closer to 90%.

There is very limited data about Gulf SMEs’ contribution to the national economy. But as SMEs on average pay lower wages and run less capital-intensive and lower-margin operations than larger companies, their share in private economic activity is lower than their share in private employment, possibly as low as 30% – considerably less than in the EU, where the share is closer to 50%.

There are many impressive individual stories of innovation and growth among Gulf SMEs. Yet, a large share of the great mass of SMEs still contributes fairly little to diversification and national employment. What are the factors that hold back Gulf SMEs’ role in economic modernisation?

Challenges

Many SME development issues in the Gulf resemble those of the developing and developed world more generally; others are more particular to the Gulf.

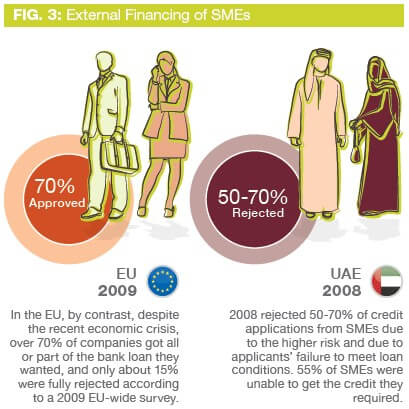

One well-known generic problem is getting financed: According to a study by Dun and Bradstreet, banks in the UAE in 2008 rejected 50-70% of credit applications from SMEs due to the higher risk and due to applicants’ failure to meet loan conditions. 55% of SMEs were unable to get the credit they required. In the EU, by contrast, despite the recent economic crisis, over 70% of companies got all or part of the bank loan they wanted, and only about 15% were fully rejected according to a 2009 EU-wide survey.

One of the reasons why local banks may avoid SME exposure is the relatively larger administrative effort. More often, however, loan requests are rejected for good reasons: Accounting skills of many SME managers are rudimentary; business and feasibility plans are frequently lacking. The enforcement of collateral in local courts, moreover, can be slow.

The delegation of daily operations to expatriate managers – especially in the smaller and richer Gulf countries – tends to limit innovation and the acquisition of skills among SME owners. As long as a regular stream of income can be created with low-margin activities and low effort from the owner’s side, reluctance to innovate and take risks will remain widespread among small companies.

Business behaviour in the Gulf also tends to be fairly individualistic, with limited cooperation on purchasing, supply chains and marketing by SMEs of all sizes. A lack of business planning and low margins can also mean that access to talented manpower is limited. SMEs tend to offer low wages and no career plans and long-term prospects for their employees.

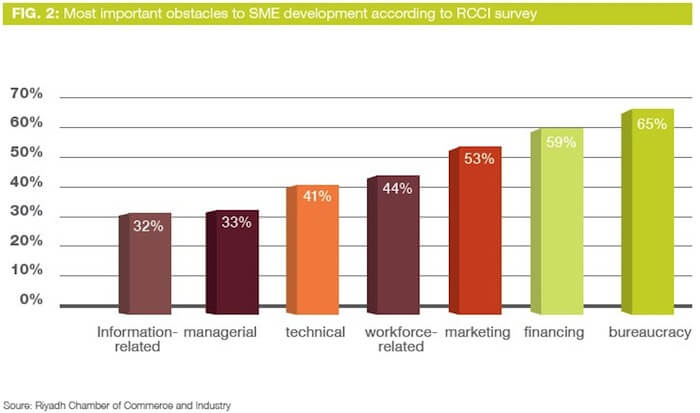

SME management also continues to spend much energy on dealing with local bureaucracies: While the investment environment in the GCC has become smoother for larger investors, it often remains cumbersome for smaller players. This makes business less predictable and hence works against long-term investment. A study by the Riyadh Chamber of Commerce shows bureaucracy as the most important obstacle to SME development in Saudi Arabia:

Governments have taken up the challenge of SME development. Numerous support programs have been rolled out during the last decade. They remain fragmented, however, and few follow-up studies and systematic evaluation of policy outcomes are undertaken. The innovative models of incubation and business services developed in some regional institutions, could be done better justice by creating such reports.

One could criticise that too many support programs still provide direct subsidies financing viable and non-viable ventures without discrimination; some of them also offer services that would be more easily provided by private business service companies.

SMEs as family companies

Almost all SMEs in the GCC are also family companies; SME challenges, hence, are family business challenges. The converse is also true: SMEs face the typical family business issues of sorting out the distinction between ownership and management, building succession plans, separating family from company finance and many more.

Family dominance can make it hard to attract qualified non-family managers. The centralisation of power in many family businesses can also push talented family members to leave the company, further complicating SMEs’ human resource quandaries.

Fluid, low-margin company structures mean that often there is little to hand over to the next generation. Family links provide trust, but when they are supposed to substitute for formal governance structures, the result is often the demise of the company as soon as family circumstances change. The average age of Saudi SMEs is 7 years, reflecting a low survival rate. Governance reforms in Gulf SMEs are recommended not only to move them towards higher value-added production, but also to preserve family wealth.

The need for higher value-added

The challenge for Gulf SME sectors is not aggregate, quantitative growth – that has been achieved with ever-growing imports of foreign labour, with relatively small long-term benefit for the local population. The challenge rather is qualitative growth into technologically and managerially more sophisticated sectors that allow for product differentiation, higher returns and salaries that are sufficient for national employees. The current paradigm of SMEs that are all providing the same low-margin services and products should be overcome in order to achieve this goal.

Some of this change has to come from within businesses; but on some levels, governments could help, for example by:

- Designating national lead agencies to coordinate and benchmark SME support policies, consolidate available information, and make it publicly available.

- Focusing support policies exclusively on sub-sectors with higher value-added that can provide national employment.

- Orienting SME support programs towards the provision of an enabling environment for SME growth rather than subsidised credit and free business support services.

- Fostering cooperative structures among SMEs in marketing, procurement and the sharing of infrastructure and business services.

- Measuring the performance of existing support programs, notably through controlled trials, and publishing the results.

- Establishing dedicated SME support windows in government agencies.

Under the right circumstances, small Gulf business families can become the main drivers of diffuse diversification and national employment. In Europe, companies with up to 250 workers contributed a full 85% to employment growth from 2002-07. An enlightened SME policy is a crucial ingredient for stemming the socio-economic challenges the young and underemployed populations of the GCC will face in coming years.

Tharawat Magazine, Issue 10, 2011