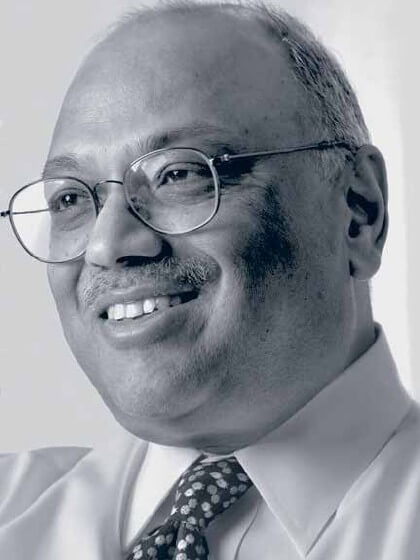

This article is dedicated to the late Prof. C.K. Prahalad, globally recognised scholar and consultant to top managers. He left a rich legacy of academic research, strategic next practice, and innovative theories. In memory of a great thinker and to honour the great work he left to the international business community and academia, we apply a few of his numerous theories to the practice of Arab family businesses.

Professor C.K. Prahalad

Born in South India as the son of a Sanskrit scholar and judge in Chennai, C.K. Prahalad began his academic career at the Indian Institute of Management, and then went on to pursuing his doctorate at Harvard Business School. He was appointed to the position of Paul and Ruth McCracken Distinguished University Professor of Corporate Strategy at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business in the University of Michigan. Prof. C.K. Prahalad was an inspiring scholar to say the least. Throughout all of his publications he aims for sustainability and a positive social impact, through responsible management with a particular focus on the bottom of the economic pyramid. Dedicating most of his research to corporate strategy, he was one of those great thinkers, who may have suffered from that ailing phenomenon of ‘being ahead of his time’.

C.K. Prahalad on Dominant Logic

(Based on the article The Blinders of Dominant Logic, C.K. Prahalad, Long Range Planning Journal, 37, Elsevier, 2004)

In his theory on dominant logic, C.K. Prahalad explains the fixed mind sets in organisations that are shaped through management practice, business models, approach to competition and successful work processes. The dominant logic of a company is what keeps it focused and, at the same time, blinds into Prahalad calls the periphery. Therefore being able to change the dominant logic in a company means opening it up to new opportunities and innovation that it cannot recognise in its current vision. This change of perceptions can help recognising real customer needs and competition in time. ‘The dominant logic of the company is, in essence, the DNA of the organisation.’ Prahalad writes. Therefore, we can easily understand that changing the dominant logic of a company is difficult and may require surmounting a considerable amount of resistance internally. Yet, it has to be done, as in a rapidly changing economy sticking to a dominant logic is synonymous to rigidity.

The clear argument that Prahalad presents, advising companies to change their dominant logics, consists in the new type of value creation we are facing. ‘The interface between the company and the consumer is the locus of economic value extraction.’ Prahalad explains. Value creation is no longer reserved to products and services but is increasingly experience-based. Dominant logic and value creation through experience are not compatible, as value creation through experience demands the view to the periphery, which dominant logic usually prevents.

Experienced-based value creation is built around four facts, also known as the DART:

• Dialogue: Today’s consumer has become a part in creating the product strategy.

• Access and choice: Rewarding customers’ enthusiasm for products and services by giving them easy access to it impacts on brand equity.

• Risk assessment: Customers now have the information to assess the risk of their decisions without always having to consult external expertise.

• Transparency: Customers want to see how things are done and be part of the product development and production.

All in all, Prahalad suggests a shift from fixed value chains to more flexible value creation webs. Consumers should be considered co-creators who pick their mode of interaction and the channels they want to use (for example a banking customer can pick an ATM, a PC, or a branch to get almost the same services). There are, therefore, new demands for value creation:

• The need for experience network

• The need for intelligent products/services

• The need for dialogue, access and transparency

• The importance of consumer communities

• The need for real time action

• The need to cope with heterogeneity and complexity

• The need for alliances

• The need for rapid reconfiguration of resources

It seems clear that such experience-based value creation does require innovation and open-minded attitudes from businesses. Changing the dominant logic regularly has become an imperative. Rethinking the logic of the business might include taking a look across borders into new markets and technologies.

Nowadays it is not enough for a business to focus on best practice; best practice only benchmarks on existing ideas and dominant logics that are already there. Prahalad advises to think of next practice instead: companies should try for what no one else has done before and go for a whole new approach.

Companies that are able to challenge the dominant logic see how they can make money even in emerging markets where people make only a couple of dollars a day.

‘The dominant logic of our companies, like blinders on a horse, allows organisations to perform well at their current task in the short term. This logic keeps us focused on the road ahead, but also limits our peripheral vision. In a world in which many new opportunities are opening to the left and right of the beaten paths, we need to recognise the limitations of the dominant logic and look for ways to apply different logics to value creation and the organisation of our companies.’ C.K. Prahalad

Dominant Logic in Arab Family Businesses

Family businesses are the ideal candidates to fall victim to dominant logics. Indeed, in family businesses the dominant logic is often set by the core businesses that have run successfully for decades and also by the founder’s vision. While these should not be discarded, it can be seen how pursuing this track over a long period of time could become detrimental to family businesses. For a family business often the idea of shifting away from such well-known patterns of management and doing business seems like treachery to the family values and to the achievements of the previous generations. It should be possible, however, to distinguish between necessary strategy revisions, innovation, and the downright giving up of values.

The need to move away from an existing dominant logic is underlined by the current trends: Arab family businesses like the rest of the world are confronting the new ways of value creation. Prahalad’s suggestion that value is created based on customer experience rather than on products and services, is shown by products such as I-phones and other integrated devices. Arab family businesses have to ask themselves if with their current way of doing business they actually can cover the new demands of value creation that Prahalad mentioned.

Should they fail in one or several of these aspects it is high time to understand that the current dominant logic is blending out necessary recognitions about the business.

Most family business members will immediately feel the challenges implied in trying to change the dominant logic of their companies. The mindsets that have been there for a long time not only in the business but also in the family create hurdles that are hard to overcome. However, family businesses also have an in-herent ability to challenge dominant logic: succession.

When a new generation join the business or later take over, the family gets what Prahalad calls next practice, for free. Dominant logic can be challenged from within and from outside the family business. Sticking to a dominant logic and blinding out the periphery does not only mean ignoring market trends but also failing to consider the input of certain family members, which can create family conflicts. Mostly, whether or not the dominant logic in a family business is unchangeable will depend on the attitude of the family business leader. If leadership dictates innovation getting locked up in a dominant logic cannot happen, not even in a family business that has outlasted many generations.

C.K. Prahalad on the Co-creation of NGOs and MNCs

(Based on the article Co-creating Business’s New Social Compact, Jeb Brugman and C.K. Prahalad, Harvard Business Review, February 2007)

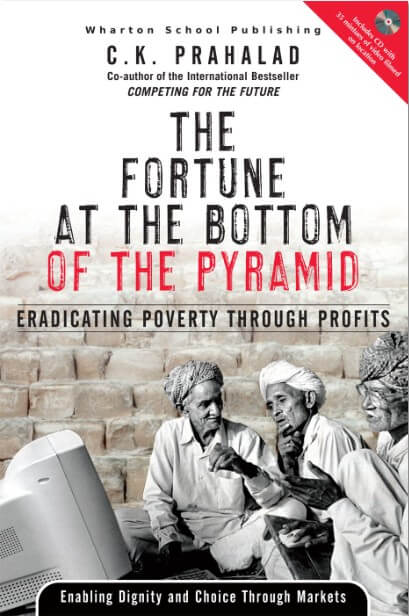

How do I make money off a consumer that earns less than $2 a day? The question seems unethical and, yet, is probably one of the most efficient ways of fighting poverty ever developed. In C.K. Prahalad’s book ‘The fortune at the bottom of the economic pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits’, published in 2004, he underlines that companies should take a closer look at the fact that two thirds of the world population are actually situated at the bottom of the economic pyramid. The low-income market, contrarily to what we might think, actually represents a pool of opportunities and purchasing power for companies.

Tapping into the customer segment that is situated at the bottom of the pyramid requires, however, deep knowledge about societal structures and dynamics. For a multinational company this knowledge is hard to come by but is mandatory in order to adapt marketing and management of new services and products offered.

To remedy this gap in knowledge, MNCs (Multi-National Companies) have started associating themselves with NGOs. Prahalad explores the convergence between MNCs and NGOs and their subsequent co-creation.

‘The liberalisation of markets is forcing executives and social activists to work together. They are developing new business models that will transform organisations and the lives of poor people everywhere’. C.K. Prahalad and Jeb Brugman

The idea of corporate companies and NGOs being directly opposed to each other’s visions and goals is fading as we see more and more collaborations between the two sides emerging. While NGOs are sharply opposed to the effects of globalisation and therefore would have liked to see reforms in favour of protecting low-income markets, many corporations see their interest in pushing reforms to becoming even more accommodating to liberalisation. The definition of how a socially responsible enterprise should operate is a difficult one.

Over the years it has become increasingly apparent how NGOs and MNCs depend on each other. Their cooperation happens at the level of the low-revenue consumer. NGOs can give corporate companies access to knowledge about markets that they usually could not tap into, while corporate companies can show NGOs a lot about the professional management of their operations.

Where did this convergence come from? Not so long time ago, the notion of responsible corporations robbed the spotlight from profit maximisation at any price. Many corporations saw themselves forced into CSR activities more as part of a reputational rescue campaign than as an actual strategic focus. We can see in table 1 how the convergence took place step by step. However, this new orientation towards responsible ways of doing business opened up a whole new world of opportunities focused on the consumers situated at the bottom of the economic pyramid.

On the other side, NGOs have started to build up businesses that provide the jobs and means for poor people to support themselves. There is the example of Accion that acts as an agent for large microfinance NGOs, and has loaned $9.4 billion to 4 million people in 22 countries with a repayment rate greater than 97%.

‘As their interests and capabilities converge, these corporations and NGOs are together creating innovative business models that are helping to grow new markets at the bottom of the pyramid and niche segments in mature markets.’ C.K. Prahalad and Jeb Brugman.

The best way to fight a phenomenon that has a negative impact on society is by making its solution profitable. Prahalad and Brugman’s approach towards co-creation between multinationals and NGOs shows one of the ways that this can and has be done.

Co-creation for Arab family businesses and NGOs

Catering to the bottom of the economic pyramid is something that Arab family businesses already do. Indeed, Arab economies hold the entire spectrum from very wealthy to very poor population segments. The low-end earner represents a larger share of the consumer market and therefore cannot be ignored as a consumer.

In the region, it is well-known that family businesses tend to own their own CSR activities and NGOs. It is part of most companies’ vision to support the community and often falls under zakat or other philanthropic activities. The family, being the owner of both the business and the civil service unit, eases direct decision-making and can turn social best practice into reality.

It could be claimed therefore that the convergence Prahalad speaks about is already at a very advanced stage, when it comes to Arab family businesses. Still, a professionalization and consolidation of socially responsible activities in the region could be achieved through family businesses collaborating on this front. Alliances on the CSR front between family businesses could be the way to go. Arab family businesses could become trend-setters when it comes to the convergence between corporate culture and social responsibility.

‘When companies have succeeded in bottom-of-the-pyramid markets, we found, they have most often done it by leveraging the competencies, networks, and business models that were developed as part of their CSR activities or by NGOs.’ C.K. Prahalad and Jeb Brugman.

What Prahalad shows is that a lasting social impact can be created through no longer seeing the poor as a charity case but by creating opportunities to help themselves.

We thank him

C.K. Prahalad passed away in April this year at the age of 68. He left behind a rich legacy to the business community and academia. He showed us that there does not need to be a trade-off: there can be profit without exploitation.

Prahalad was a man, who knew the world could be a better place and who dedicated his life to creating the solutions that will help humanity achieve this goal.

‘Really, in all my career I have been interested in ‘next practices’, and not merely ‘best practices’.’ C.K. Prahalad to the Financial Times