Image Source: Aleksandar Pasaric from Pexels

Facts and Figures on Arab Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Arab countries are heavily dependent on global trade, have a great degree of trade openness, and their inward FDI stocks compared to GDP are high by international standards. This seems to fly in the face of conventional wisdom, which portrays them as closed and inclined towards protectionism. While such views reflect the old nationalist rhetoric and import substitution policies that were prevalent in yesteryears, they are in need of a qualified revision. Dr. Eckart Woertz from the Gulf Research Center, Dubai, provides facts and figures on Arab FDI, explains the economic trends, and why intra-regional investment is still scarce.

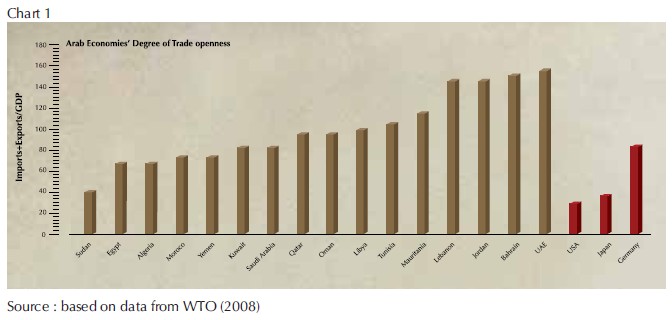

Openness to international trade can be measured by the percentage of imports and exports to GDP. Even the Arab country with the lowest ratio of trade openness, Sudan, is still considerably above OECD countries like the USA or Japan. While Sudan has a degree of trade openness of 43, the US has only 27 and Japan only 31. All other Arab economies have an even higher degree of trade openness, with the United Arab Emirates at the top with a level of 159 (see chart 1).

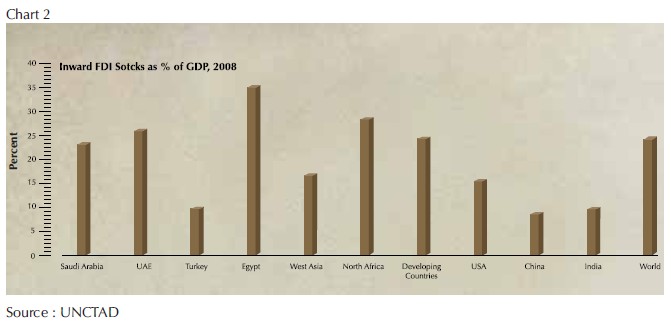

The same picture emerges if one takes a look at the ratio of inward FDI stocks to GDP. With around 25 percent Saudi Arabia, the UAE and North Africa are on par with developing countries worldwide and way above the levels of the USA or China, whose share is 16 percent and 9.9 percent respectively. The ratio is particularly high in Egypt with 37 percent; even the West Asian countries of the Arab world command a share of 18 percent and are thus considerably above emerging markets like China and India (see chart 2).

However, such openness does not necessarily mean dynamism and prosperity as the now bruised economic orthodoxy would suggest, nor has it led to a high degree of economic integration within the Arab world. According to the WTO the intra-regional share of trade in the Middle East in 2006 was only 11 percent; only Africa ranked lower worldwide.

The simple explanation is that the Arab region is structurally extroverted; it is huge by geographical extension and sparsely populated – two characteristics that discourage the intensification of intra-regional trade. Casablanca and Dubai are separated by 6000 kms of mostly empty desert land, while the distance between Lisbon and Moscow is only 4000 kms with densely populated areas and well developed infrastructure between them. Furthermore, Casablanca is only 800 kms away from Madrid. Not surprisingly, trading relations of Maghreb countries are primarily with Europe and not with fellow Arab countries – 60 percent of Morocco’s external trade is with the EU, for Tunisia the EU’s share even exceeds 70 percent.

Apart from being geographically vast and sparsely populated, the Arab region often lacks a sufficiently modern communication infrastructure. It is easier to fly from Dubai to London than from Cairo to Tripoli. The Gulf countries are an exception as they were able to invest in a tightly knit road network and have now started to establish rail links along major traffic corridors. Otherwise in many Arab countries the quality of road and rail connections rapidly declines as soon as one leaves the immediate surroundings of the capital city. Thus, transporting goods from one Arab state to another is not an easy task, and frequently political relations and complex customs procedures complicate it further. Maritime-based trade over long distances is often easier than short haul exchanges via land.

It also has to be kept in mind that many Arab countries are still predominantly exporters of raw materials and rather compete with than complement each other. Certainly, some Arab countries like Jordan or Lebanon do not have oil or gas at all and have tried to specialise in niches by providing goods and services to their neighbouring countries. But overall, resource extraction is an important factor even in less well-endowed economies like Egypt or Syria, which limits the potential for complementary trade at this stage.

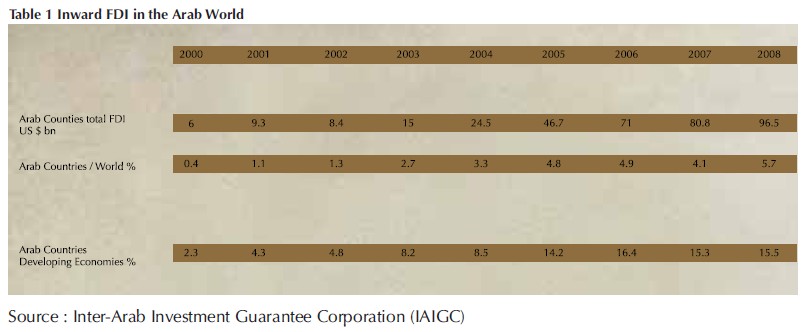

Structural factors compounded by conflicts between neighbouring Arab countries have discouraged intra-regional trade and have led to the most outward oriented region in the world. This also applies to FDI in the Arab world; it has increased sixteen-fold between 2000 and 2008. Especially after 2004 it has grown strongly, spurred, by high oil prices and an improved investment environment. Tariffs have been reduced in the wake of the GCC customs union 2003 and the GAFTA (Greater Arab Free Trade Area) in 2005 and with Saudi Arabia the last GCC country joined the WTO in the same year. Growth was not only in absolute terms; the share of Arab FDI relative to the world total has increased from 0.4 percent in 2000 to 5.7 percent in 2008, relative to developing countries it has grown from 2.3 percent to 15.5 percent over the same period (see table 1).

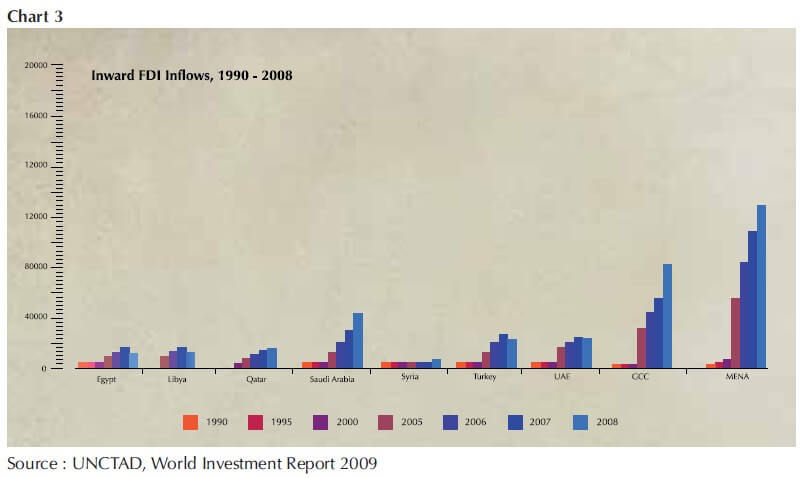

This growth has been focused on a few countries in the Arab world, namely Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar and Egypt, which represent about 70 percent ($68 billion) of total inward FDI in the Arab world (see chart 3 below). A middle group of countries like Libya, Lebanon, Jordan, Oman, Sudan, Morocco, and Tunisia also attracted substantial sums of FDI in the range of $2.5 billion to $4.1 billion in 2008. In comparison, the Palestinian Territories, Yemen and Iraq were underperformers when it came to FDI. Syria attracted more substantial FDI of $2.1 billion in 2008 after it had been an underperformer in earlier years. Contrary to its oil-rich peers, Kuwait only attracted FDI of $56 million in 2008, which can be attributed to an outspoken rentier bias of its economy and some difficulties in implementing major investment proposals.

It is striking that there is such a concentration of FDI in hydrocarbon-rich countries. Even in less well-endowed countries like Egypt or Sudan, a large share of FDI went into the oil and natural gas industry. The upstream oil industry in GCC countries is mostly closed to FDI, but large investments have been undertaken in the downstream sectors of petrochemicals and refining. Energy intensive industries like aluminum have also been a focus of FDI in the GCC countries. The Petrorabigh refinery of Sumitomo and Aramco or the Qatalum Aluminum smelter of Norwegian Hydro and Qatar Petroleum are cases in point. The global hike in energy prices has supported a shift of energy-intensive industries to the Gulf region and has prompted corresponding FDI flows. Other sectors that have played a considerable role in FDI in the Arab world have been telecoms, banking and construction.

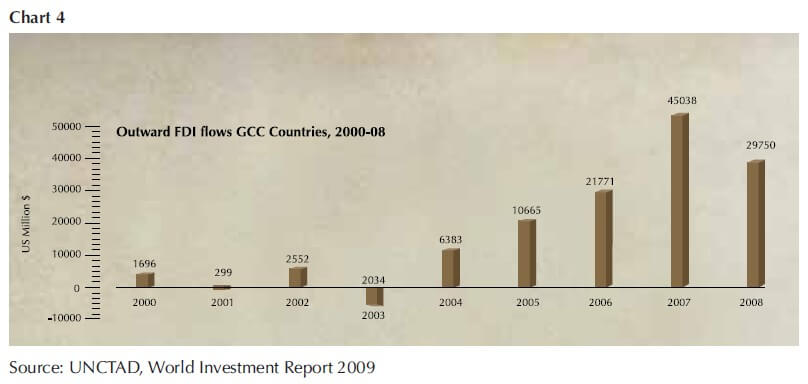

The Arab world has also seen a steep rise in outward FDI as a result of the oil boom in recent years. FDI of the oil-rich GCC countries started to skyrocket from 2004 onwards and peaked at $45 billion in 2007 (see chart 4 below). Some of this money has been flowing to fellow Arab countries. The Inter-Arab Investment Guarantee Corporation (IAIGC) estimates that the share of inter-Arab FDI in overall FDI in the Arab world grew from a quarter to a third between 2007 and 2008. While this is an impressive figure, a majority of inward FDI in the Arab world still comes from non-Arab countries. As the Arab world is open to trade, but mostly trades with the outside world the same is true for FDI, although to a lesser extent.

The growing role of inter-Arab FDI reflects considerable improvements in regulatory frameworks, transparency and governance. These developments have been conducive to FDI and many countries in the Arab world have moved up the international competitiveness rankings in recent years. During its boom years, Dubai has not only attracted many international real estate investors, but UAE-based companies like Emaar also eyed investments in real estate in other Arab countries such as Morocco, Egypt and Syria. Kuwait’s Zain acquired mobile licenses in many Arab and African countries, and Commercial Bank of Qatar acquired a stake in National Bank of Oman. Dubai Islamic Bank and National Bank of Abu Dhabi on the other hand have invested in Jordan just to mention a few examples. There have also been investments in the manufacturing industry: Saudi Arabian Savola invested in a fertilizer company and a sugar refinery in Egypt for example. Even some agricultural investments have been announced, although the potential is limited as the whole MENA region suffers from a dearth of water. Abu Dhabi-based Al Qudra has eyed agro projects in Algeria and Morocco while Saudi-based Al Rajhi is invested in Egypt.

Still, the structural limitations of economic integration in the Arab world that have been outlined in the beginning take their toll and intra-Arab economic integration is relatively low. A major motivation for FDI in the Arab world remains cheap energy feedstock, while other classical motivations like access to large domestic markets, cheap or highly qualified labour and favourable investment conditions weigh less in the balance. However, with growing economic diversification the opportunities to trade may increase and FDI will follow commerce like elsewhere. The GCC, which is arguably the most successful effort at Arab economic integration, has witnessed a steady rise in intra-GCC trade since the inception of its customs union in 2003. With further diversification, infrastructure improvement, and continuous political will enhanced steps at Arab economic integration may well be on the cards in the future.