Emotional relationships (positive and negative) have a powerful influence on every aspect of our lives and are a key influence our behaviour and decisions. Behaviours driven by emotions can be dysfunctional, especially if based on feelings founded on false assumptions about another person. In a business setting, for example, an individual might assume that a colleague is jealous of his success and wishes to block advancement, in which case the individual might be uncooperative and even destructive about the colleagues’ work. In fact, the individual might well have been more successful had he assumed that the colleague had the emotional intelligence to help facilitate success for both parties involved. Either way, the emotion remains unspoken, the assumption remains untested and the outcome remains suboptimal.

By Professor William Scott-Jackson, Robert Mogielnicki, Lorraine Charles, and Rasheeda Haddish. This article is based on Oxford Strategic Consulting’s latest research initiative on ‘Leadership and Governance in GCC Family Firms.

[ms-protect-content id=”4069, 4129″]

Family Business Emotions

Family businesses tend to reflect the kinds of emotional relationships that are more typical of families themselves (for example a father may feel conflicting emotions about a child such as love or pride versus the underestimation of their abilities), as well as the emotions that might occur in non-family businesses (e.g. in-fighting over positions, jealousy etc.). It might also be assumed that close relatives (e.g. parents and offspring) have heightened inter-personal emotions because they care deeply about each other’s feelings and about how they are perceived by each other. These emotional links can present advantages for family firms, as they can inculcate loyalty, mutual understanding and trust, but they can also lead to misunderstandings and have a negative impact.

Even more than in other social groups, families may be less likely to express negative assumptions or emotions, and this is particularly evident in collective societies, where the importance of maintaining good relations leads to an avoidance of conflict and the suppression of any negative feelings to others. While this is advantageous in many ways, it does mean that it is difficult to resolve underlying causes of negative emotions as they are unexpressed and therefore unknown. Moreover, the family unit and loyalty to it, is central to the functioning of collective societies. The strong sense of loyalty that exists in families in collective societies has been translated to their family businesses and can be expressed in many different ways. For example, there may be fewer family conflicts because there is deference to the opinions of elder family members or trust in the intentions of younger members. The issue of including offspring in family businesses these societies may be less problematic as the sense of loyalty to the family implies an expectation on both sides (older and younger generation) that there will be continuity of the business.

The question arises, why we need to worry about emotions in the cold and logical world of business. Management, economic theory, and best practice (especially in the US and west) has, until recently, been predicated on a purely rational and non-emotional view of business, but this perception is fast-changing with a new understanding of the key role (positive or negative) that emotions can play in every aspect of personal, social and business life. Through research we were able to identify some of the positive and negative emotions typically expressed in family firms, particularly at key growth stages, and most often in response to other key players. This research indicates that emotions play a particularly strong role in the running family firms.

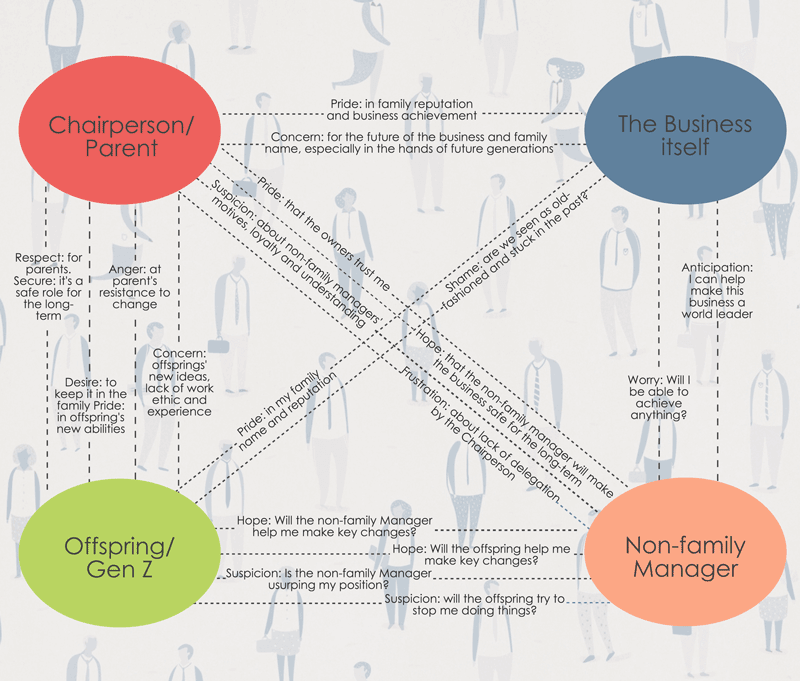

The Emotional Network

These commonly encountered emotions can be illustrated according to the subject or rather the person who has these emotions, and the object, the person or thing representing the focus of these emotions. In the emotional network (Figure 1), we identify the following main players:

Chairperson/parents – the older generation, who identify strongly with the family firm and its founder, understand and maintain traditional goals, leadership styles and identity, and who have a strong sense of family identity and cohesion.

Offspring/Gen Z – the younger generation who have been heavily influenced by global shifts in social technology, new career aspirations, a more questioning approach to norms and work-life.

Non-family Managers (N-fM)– members of the management team who do not belong to the family. Often not really part of the informal inner circle of family members.

The business itself – in most cases the business itself becomes the object of emotions and can therefore not be left out of this construct. Naturally, the business can merely be an object not a subject in this case.

The emotional network within a family business is illustrated in figure 1, and includes some of the more commonly expressed emotions we have noted in our research.

As noted above, in most of the family business we have researched so far, the general trend is not to express or discuss negative emotions. Whilst this can defer open conflict, it also eliminates any possibility of resolving the underlying issues. Our recommendation, therefore, is to utilise the positives and resolve the negatives. In order to resolve the negatives, it is crucial to understand what they are, but it is not feasible for the family to discuss these issues openly with each other. An independent survey or interview process, with the objective of solving any issues, could be the best solution (see below). In fact, our research interviews have demonstrated a refreshing honesty and openness to discuss issues with an independent trusted third party.

Examples of Negative and Positive Emotions

Once emotions are identified within the family business, the question remains as to how negative emotions can be addressed by solutions, and in what ways positive emotions can be used as a positive leverage for the business:

Solving cases of negative emotions

Emotion: Chairperson/Parent feels concern about Offspring’s new ideas, lack of work ethic and experience.

Solutions:

- Teach offspring how to present a business case, introduction to work-life and obligations, change management skills and strategic decision-making.

- Use a small change as a test-bed and get Chairperson/Parent and Offspring to analyse how it went, their feelings and so on.

- Define specific role for Offspring in innovation, special projects, new product areas.

Emotion: Offspring is worried that N-fM is usurping their position.

Solutions:

- Ensure clear role definition for N-fM and Offspring and set up a joint project to build their relationship.

- Chairperson confirms the importance and role of Offspring and/or explains the need for the N-fM and their importance for the success of the Offspring.

- Ensure any N-fM is assessed to ensure they are personable with high emotional intelligence as well as capabilities.

Leveraging on cases of positive emotions

Emotion: Offspring is proud of the family and its achievements:

Leverage:

- Assign Offspring to external communications or public relations role.

- Allow Offspring to have high involvement in marketing.

Emotion: Non-family Manager hopes that Offspring will support changes.

Leverage:

- Create mentoring relationship between non-family Manager n-fM and Offspring.

- N-fM to provide knowledge and support in best practice management, Offspring to guide N-fM in family and local culture. Make them a small team.

Emotion: Chairman/Parent is proud of Offspring’s new abilities

- Devise a role involving new media, technology exploitation or in the area of the Offspring’s particular new abilities.

- Give them a new business budget authority.

In Conclusion

Our research demonstrates that family firms can harbour enormous competitive advantages and that these are inherent in the close relationships, trust and understanding between family members. The involvement of emotions within family businesses can provide a strategic advantage, particularly within collective societies due to the cultural importance of family structures. While, it is acknowledged that specific disadvantages can also result, these can be mitigated through systematic processes. As organisations grow they need to increase process management, governance and the employment of non-family managers in order to meet these growth demands. All this is possible without destroying or disregarding the unique strengths of the family business, provided that the crucial network of relationships and emotions is understood and managed effectively.

Tharawat Magazine, Issue 25, 2015

[/ms-protect-content]