By Prof. Dennis T. Jaffe and Dr. James Grubman

Every business family has a unique character. Yet, each family business springs forth from a cultural tradition that expresses the values, thinking, and behaviours of its homeland. Enterprises achieving success often expand to new environments, encountering families and businesses with different values from diverse cultures. What they most value and how they build relationships, solve problems, and negotiate may be radically different. To prosper, the business must cope with these differences, developing cross-cultural competencies.

Affluent business families also encounter outside cultures as they travel, establish international residences, and especially, send children to other countries for education and work experience. The younger generation absorbs the ways of foreign cultures, with an inevitable desire to introduce these to the family at home. Older generations – unhappy with new ideas straying too far from traditional ways – may in turn respond sceptically. Cross-cultural pressures within family life then require their own form of negotiation and compromise.

It is crucial that business families are aware of predictable stresses likely to surface as the enterprise expands beyond their home culture. We offer a new perspective on the changes advocated by the rising generation, exposed to a cross-cultural education, and what families can do to adapt successfully to this challenging process.

The Powerful Influence of Culture

Cultures in different regions of the world generate various patterns influencing business families as they integrate personal relationships, parenting, and commerce:

“Culture is the unique character of a group. Individuals have personalities; groups have cultures. You can see culture in the pattern of people’s beliefs, attitudes, norms, and behaviours as well as in the nature of the social, economic, political, legal and religious institutions that structure and organise groups. Anthropologists suggest that culture emerges because people are faced repeatedly with similar social problems.” Jeanne Brett, noted specialist in cross-cultural negotiation

Cultural differences influence how people act within the family and the business, what they expect from the next generation, and how they talk to each other.

The Three Major Global Cultures

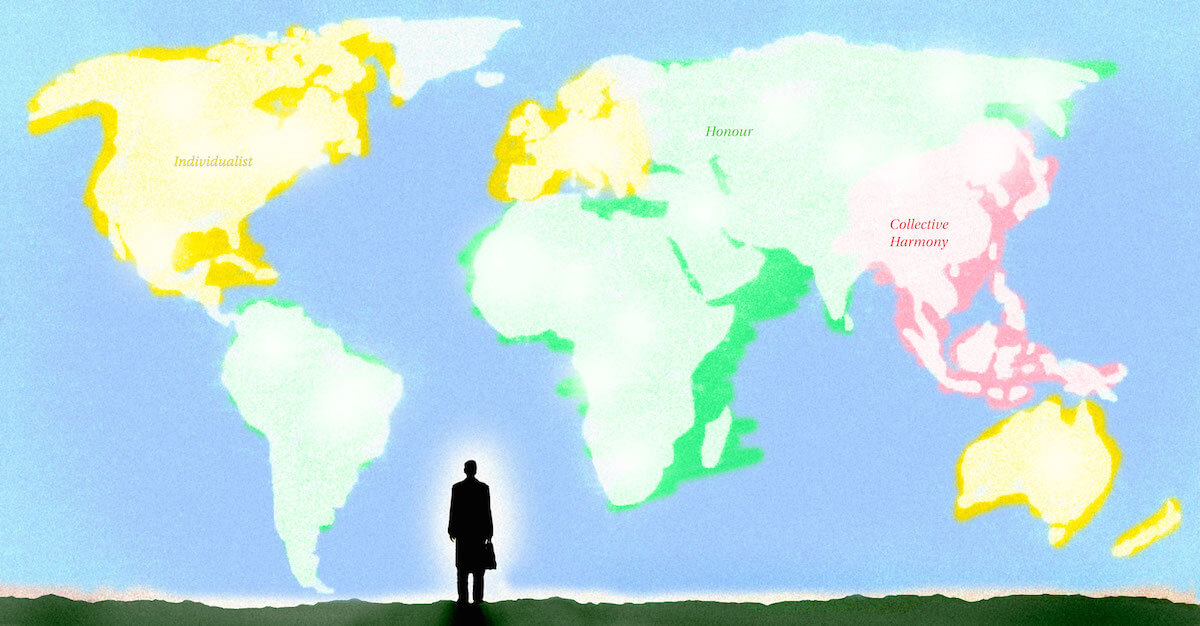

While every country and ethnic group has a unique character, cultural theorists have defined three broad global patterns of family culture. Each tradition incorporates cultural patterns that influence the expectations, practices, and behaviour of family enterprises in those regions (see map at the top).

Individualist Culture: Rational Thinking and Personal Dignity

Northern Europe, North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia share a style steeped in individualism, rationalism and the promotion of human dignity. The individual is pre-eminent, with business and family supporting personal independence and dignity. The purpose of the family is to help each member develop a fulfilling life, maximizing potential; children are praised for accomplishments and expected to seek their own path. Individualist culture is about meritocracy, accountability, individual achievement, rationality, and visible success through hard work.

Leadership exalts the lone individual operating within a strong team of competitive but committed peers. The leader’s legitimacy must be earned via the trust of his followers or risk removal. A leader’s authority is tempered by the overriding rule of law that guides decision-making, insures fair dealings, and counters overzealous attempts to grab power. Men and women are presumed to be equal.

Business communications are to be rational and non-emotional, though within relationships the open expression of feelings, thoughts, and ideas is widely accepted. The business informality of the US demonstrates egalitarianism where people eschew titles in favour of using first names.

Transparency, sharing of ideas, and valuing of innovations from the rising generation is encouraged – the voices of youth can be heard and heeded. The rising generation feels entitled to question elders rather than dutifully accepting guidance. Stanford University professor T. M. Luhrman notes:

Americans and Europeans stand out from the rest of the world for our sense of ourselves as individuals. We like to think of ourselves as unique, autonomous, self-motivated, self-made. As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz observed, this is a peculiar idea. People in the rest of the world are more likely to understand themselves as interwoven with other people — as interdependent, not independent. In such social worlds, your goal is to fit in and adjust yourself to others, not to stand out.

People imagine themselves as part of a larger whole — threads in a web, not lone horsemen on the frontier. In America, we say that the squeaky wheel gets the grease. In Japan, people say that the nail that stands up gets hammered down.

The major risk is that, by embracing youth, individualism, and innovation, Individualist culture risks devaluing tradition, loyalty, and established wisdom. The authority of elders and family may be neglected. Individuals are less willing to compromise for collective goals, so long-term family objectives can be lost.

The call to remain united as a family is weaker, since each member can choose whether participating in the family enterprise is in their self-interest. Other cultures view Individualism as too “me-oriented,” lacking focus on the collective “we.”

Collective Harmony Culture: A Focus on Family, Tradition, and “Face”

Collective Harmony cultures, evolving over three millennia in East Asia including China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea, and Japan, are premised on Confucian principles elevating loyalty and obligation to family, respect for parents and other authorities, knowing one’s place, and supporting the whole group rather than one’s individual position.

The concept of “face” is central to Collective Harmony culture. It contains elements of prestige, honour, respect, reputation, and influence, but it is much more socially-derived and – connected than Individualist concepts of self-worth, shame, embarrassment, or social position. People respect their long heritage which has led to rules of order and harmony, not to be challenged lightly. The first question asked of any new proposal is, “What does this mean for everyone – country, community, company, family?”. People are seen as interwoven, part of a greater collective or clan.

Identity is defined by family and role. One’s task in life is to honour one’s family and live one’s assigned role elegantly. Every son and daughter has an obligation to protect and nurture the family, respect the long history of traditional wisdom, and bring distinction to the family and its reputation.

Elders are venerated. The patriarch derives authority from his place in the family order and from acting in a wise, benevolent manner. Women are respected in their assigned roles, as are young people who are to wait their turn patiently for roles of responsibility. When called upon to work for the family business, next-generation members feel obligated to respond without first discussing compensation, ownership responsibilities, or status. They would swallow any reservations about working in the family business that their Western counterparts would feel freer to question.

Communication and behaviour in Collective Harmony culture are oriented to sustaining relationships and mutual respect. Anything that disrupts family relationships is to be avoided. Language is much more ambiguous and indirect than in the West. This allows everyone to feel comfortable by not spelling out issues or concerns directly. Assertive explicit communication may tear the social network if not handled carefully, especially in families.

Strengths of Collective Harmony are its connectedness, stability, predictability, and social support. These also create its challenge: slow innovation and change. Elders may hold too tightly to traditional ideas, leaving fewer options for handling crises or seizing opportunities. They also discourage the communication and collaboration necessary to adapt in a changing world. In turn, the younger generation may hesitate to share feelings or ideas with parents and elders.

Honour Culture: A Focus on Tradition, Family and Hierarchy

Honour cultures exist worldwide as extensions of originally tribal societies in Southern and Eastern Europe, North Asia, Central and South America, the Middle East and India. The family is the social and economic centre of life, organised as a fixed hierarchy of obligation and role. More than an emphasis on harmony, there is respect for authority, with strong leaders who may be loved but are more likely to be feared and certainly obeyed. One’s place is clear from birth. Women are respected and worshiped, but traditionally women have had a limited role in Honour culture until only recently.

Many Honour societies contend with unstable institutional environments. With frequently shifting external governance structures resulting in a wavering rule of law, families and tribes learned to manage themselves and their vulnerable members. They provide stability, trust, authority, and accountability within circumstances of risk. Academic and career options as well as (in highly traditional families) marital choices are evaluated by their impact on the collective family. Excessive independence is potentially dishonourable and disrespectful to the family.

Honour families and their enterprises often possess politicised cultures based on one’s relationship with those in power. Trust is linked only somewhat to what the individual does, more so to who one knows and their history of connection to the clan. An Honour family uses known networks because a trusted partner is hard to come by. There is a small circle of deepest trust for those well-known to the family and its leadership.

Somewhat similar to Harmony culture, the downsides to Honour culture include an overemphasis on stability, potentially a lack of open communication, and behind-the-scenes power struggles. Unless the family is tolerant of adaptation, innovators strain to be heard. New ideas and new leaders must first develop credibility within the family hierarchy in order to achieve change.

The inability to discuss plans or problems collaboratively means that those lower in the hierarchy must bide their time. Compared to Harmony culture, the Honour culture hierarchy is more prone to discord. Leaders can be challenged and deposed, alliances and conspiracies can take root. Alliances do not necessarily equal real collaboration.

A Family Dilemma PART I: Tradition versus Change

A daughter from a business family with an Honour culture married and went to live in the United States where she received her MBA and worked for a large corporation. Following tradition, she left her family’s business to join her husband’s family. But the marriage fell apart. After her divorce, she wished to rejoin her family’s business and return to her home country.

Her father was open to bringing her back, but her tradition-oriented brothers were not. They felt if their sister re-joined the business, they would be diminished in the community. They also did not like the prospect of losing some of their shares and collaborating with a woman. Her father, though open to her re-joining, wanted her to live in the family compound with the rest of the family. How to reconcile the daughter’s Westernised character with her cherished roots in the family?

A Family Dilemma PART II: Negotiating the Future Together

The negotiation among daughter, father, and brothers first recognized that each of their differences was rooted in the differences between Honour and Individualist cultures. Through peer contacts in a family business network, the family learned that other Honour families were including their sisters and daughters in the business, and that next-generation family members might want to live somewhat separately from the parents. The family’s private banking advisor helped facilitate four meetings where differences and shared interests were discussed.

The resolution was that the daughter re-joined the business which adopted a Code of Conduct and set of practices that reflected some Western ideas. She would have two residences—one with family and a weekend country home near her friends.

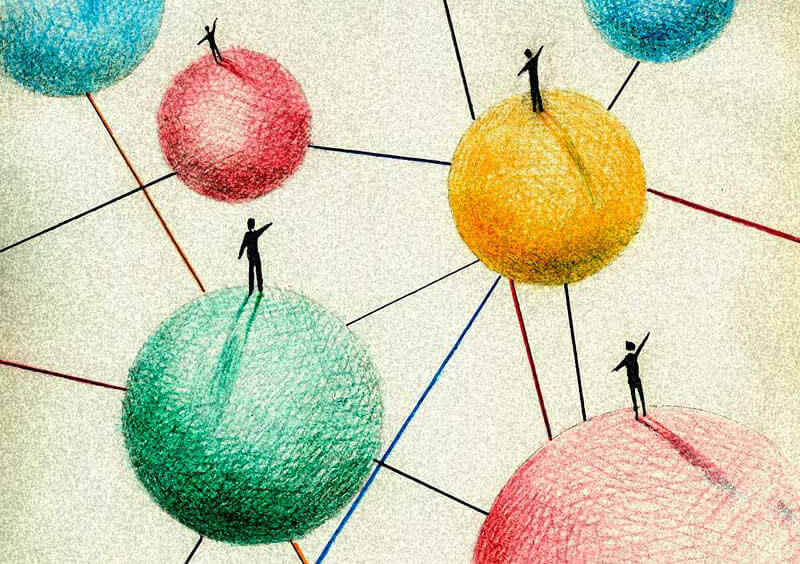

Blending Cultures in the Modern World

As family enterprises expand into the global business environment, sending children out into global cultures, families experience both the benefits and the consequences of such cross-cultural expansions. We find differences in perspective between generations or family branches often reflect culture clashes rather than personality differences. When young people talk about working as a team, exploring new initiatives, or including their siblings as equal partners, for example, they are adding ideas from their adopted Individualist culture to the traditional values of an Honour or Harmony family.

The most successful families are able to selectively incorporate perspectives of other cultures into their functioning across generations. They adapt, not by total shifts in values or style, but by being open to the best features of other cultural traditions. To achieve this harmoniously:

Elders must understand their ideas arise from their grounding in their heritage culture, in sometimes invisible ways. They can use the flexibility that fostered good business development to open their minds to the possibility of new ways within the family.

The younger generation, in turn, has to be more patient and less demanding than they might be in an Individualist culture. They must maintain respect while advocating for more open communication. Innovation cannot come at the expense of core traditional values.

Families can turn to the burgeoning network of peers and trained advisors to discover what other families are doing to blend tradition and adaptation. Sometimes the most persuasive voice comes from someone who has known – and resolved – a similar situation.

See the process as one of reasoned negotiation rather than of power or loyalty. Each family member has something to offer, to gain, and to lose. Realistically, each individual also has power in the current global world of opportunity. When families focus on their shared interests, everyone can win, while preserving the family itself.

If necessary, use trusted advisors to facilitate the negotiation and manage the delicate interplay of impassioned perspectives.

The outcome of the emerging cultural diversity is ultimately positive for family enterprises. By selecting the best ideas from each cultural tradition, family businesses can embrace each other to create a new cultural heritage.

Tharawat Magazine, Issue 28, 2015