The Japanese term monozukuri translates literally as “making things”. Figuratively, the word is similar to the English “craftsmanship” but goes further to address providence, culture and identity. Monozukuri speaks to the national pride and artisanal excellence that go into manufacturing a specific product.

In Japan, craftsmanship has been on the decline since the dawn of the new millennium. According to the Financial Times, the erosion of monozukuri is being felt by end consumers. As early as 2006, there were more than 3,400 registered product defects that either caused injury or required a recall across Japan. Just ten years earlier, that figure was a mere 1,000.

Is the dual threat of globalisation and transformative technology only affecting certain countries or is the decline of craftsmanship systemic? This question fascinates Todd Oppenheimer, Executive Director of The Craftsmanship Initiative and the founding Editor and Publisher of Craftsmanship Quarterly. His experience warrants cautious optimism about the fate of craftsmanship in the digital age. He believes that machine-assisted craftsmanship has the potential to democratise the sector and even offer opportunities for people who are not naturally gifted at using their hands.

Recently, Tharawat Magazine sat down with Todd Oppenheimer to discuss what is craftsmanship nowadays, the special connection that exists between craftsmanship and family-owned businesses and what the future of monozukuri might look like.

What is craftsmanship for you?

The most important aspect of craftsmanship is quality, which entails precision, attention to detail, beauty and integrity. Craftsmanship means putting quality before profit because as soon as a company starts to sell out, sacrificing a part of the process to make more money, craftsmanship is compromised.

Another important factor is durability: an item of fine craftsmanship should be made to last. Durability is intricately tied to the concept of sustainability in terms of resources. Ideally, we create products that are designed to last instead of needing an upgrade every year or two. In that sense, craftsmanship is the antithesis to planned obsolescence, which has become commonplace in the consumer technology sector.

How did you first become passionate about the subject of craftsmanship?

My father was a practical man. Whenever we encountered someone who seemed to be a master of their trade, he would nudge me so I’d pay close attention to the extra time and care they were taking with their work. That always stuck with me, and I gradually became fascinated with people who excel at their trades.

I soon discovered that there is a level of integrity and skill in the work people do with their own hands, which purely intellectual pursuits lack. There is a physical rigour to it – a degree of excellence that cannot be faked. Hierarchy in this world is delineated by skill. In any shop, everybody knows who the master is and who the apprentices are, and no one argues with it; it is made apparent by the work.

How did your online publication dedicated to the subject of craftsmanship come about?

I wrote an article about a master knife maker for The New Yorker about ten years ago. It gave me my first glimpse of how deep you can dive when you study a master artisan as well as how multifaceted the implications of their work are. That sparked in me the desire to write a book about the subject, but I realised that would be too limited in scope. A book would have been restricted to a few people, while the story I wanted to tell went way beyond any small collection of artisans. I founded Craftsmanship as an online magazine in January of 2015 so I could explore the topic more fully.

Your publication often explores craftsmanship through storytelling. Was that intentional from the outset?

I found that mastery and expertise develop over a long time; they are experienced chronologically. So if you are going to study those topics in depth, you cannot do it without giving it a narrative treatment.

In many cases, the artisans I write about are on a quest to master a process, and a quest is one of the oldest storytelling forms we have. The form of the magazine then fell into place very naturally.

Have you found that craftsmanship and family ownership are deeply intertwined?

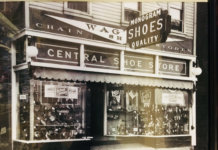

There is certainly a common thread of craftsmanship in family businesses, as many people have learned the core business processes from their fathers or grandfathers. I recently attended a workshop in shoe and boot making with a young man from Mongolia who ranks as the 14th best shoemaker in the world. He is the grandson of Mongolia’s most famous shoemaker and the benefactor of several generations of family knowledge.

Unfortunately, the attitudes of today’s consumers and young people are threatening craftsmanship around the globe. The world has become an impatient place. Most of these crafts take a significant amount of time and extraordinary patience – a virtue that young people do not generally have today. This will undoubtedly have a lasting impact on many family-owned businesses.

It is a shame because I find it extremely touching when I see family businesses successfully transition from one generation to the next. A couple of years ago, we published a story about traditional bamboo fishing pole makers in Japan who are fully aware that their trade may die with them. For many family businesses around the world, there is a real concern that the younger generation is not going to learn their crafts.

What are the implications of this erosion of craftsmanship?

Work is becoming less and less emotionally satisfying. The more technological we get, the less emotionally and psychologically fulfilled we feel at the end of the day. Today’s white-collar tech work can be challenging and satisfying intellectually, but it does not fulfil us in the same visceral or spiritual way as making a wooden spoon, a pair of shoes or even a fine meal with our own hands.

In many family businesses, it is more common to find emotional satisfaction in the work. You can almost feel your father and grandfather at the workbench where they taught you the craft.

Matthew Crawford’s book Shop Class as Soulcraft touched on this very idea. I know the von Trapp family from The Sound of Music, and they currently run a dairy farm in Vermont. One of the younger generation members refused to learn how to run the dairy farm because he did not want to take on the operation when it was his turn. Instead, he went to the city and took up a white-collar career.

After the novelty wore off, he realised he was not finding much satisfaction in this career so he went back to the family farm. He soon identified a great business opportunity and launched von Trapp Farmstead Cheese, which they started right on their dairy farm.

This all came about because a von Trapp heir had the self-awareness to recognise he was successful but unfulfilled. Fortunately, a good number of other young people are making similar choices around the world.

Today’s white-collar tech work can be challenging and satisfying intellectually, but it does not fulfil us in the same visceral or spiritual way as making a wooden spoon, a pair of shoes or even a fine meal with our own hands.

Do you see modern technology as a friend or foe of craftsmanship?

In almost any craft, there seems to be a point where the tools required to make the product and what the product should be are in perfect alignment. This is where a company reaches the apex of its quality.

Razor blades in the 1950s and 60s are a great example of this. During this era, Gillette produced the finest razors ever made, and all we have done is make them worse ever since. Fountain pens are another example. An expert told me that there used to be 75 to 100 different handwork steps in the process of making a fine pen. In both cases, as technology enabled the manufacturing process to become faster and cheaper, the quality of the product decreased significantly.

Technology and craftsmanship cannot get along mainly because technology removes us from our physical senses, which I believe to be the foundation of human skill. For a woodworker, for instance, listening to how a tool and the material interact is vital.

We recently published a story titled “Is Digital Craftsmanship an Oxymoron?” Despite technological advancements, we found that the skill of the hand and the eye is still paramount. Mechanical precision often requires a human touch to guide the machines.

That said, technology can also help democratise craftsmanship. I have a son who could never become an artisan because he is not good with his hands or his eyes. However, he loves design and, with the aid of machines, he could become an artisanal designer.

Technology and craftsmanship cannot get along mainly because technology removes us from our physical senses, which I believe to be the foundation of human skill. For a woodworker, for instance, listening to how a tool and the material interact is vital.

[ms-protect-content id=”4069,4129″]

Are modern skills, coding, for example, broadening the scope of craftsmanship?

Yes, they are. Picture a coder who will go the extra step and not give up until their program is perfect – someone who can see beyond what other programmers might see and introduce elements of quality that others may not care about. The person I have just described deserves to be considered a master craftsman. This title defines someone who has a deep understanding of quality and materials. Craftsmanship applies to many things, including technological processes.

Our documentary film, “The Future is Handmade,” suggests that scientists, technologists and engineers are tomorrow’s craftsmen and craftswomen. A lot of these people still feel a strong desire to connect to the traditional concept of craftsmanship. Another example: we know a Facebook executive who loves woodworking because he finds that he can puzzle out problems through that process – it helps him with his programming for Facebook.

What do you see when you look toward the future of craftsmanship in our society?

The artisan in his or her shop, making a handmade shoe or piece of jewellery, will increasingly be a thing of the past – they are unlikely professions for a lucrative life. However, the skills to become a master artisan in the future will start with that kind of work. That is why it is still important that we give children blocks and paint when they are two years old; it helps them develop the connections between their brain and their eyes, hands and other physical senses. Those connections are the foundations of creativity, and if we forget them, we will lose a lot of human potential.

[/ms-protect-content]