With a long, rich history in creating artisanal fabrics, Venice occupies a prominent position in the world of textiles. Integral to this legacy of traditional craftsmanship is the luxury textiles company Luigi Bevilacqua. Named after its founder, whose works adorn the walls of prestigious institutions around the world,

Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua was officially founded in 1875, although the family’s history in the textiles extends as far back as 1499.

Using time-honoured weaving techniques on original 18th-century looms, the family-run business continues to produce extravagant silk and velvet fabrics, the likes of which adorn the walls of ancient castles and aristocratic homes across Europe.

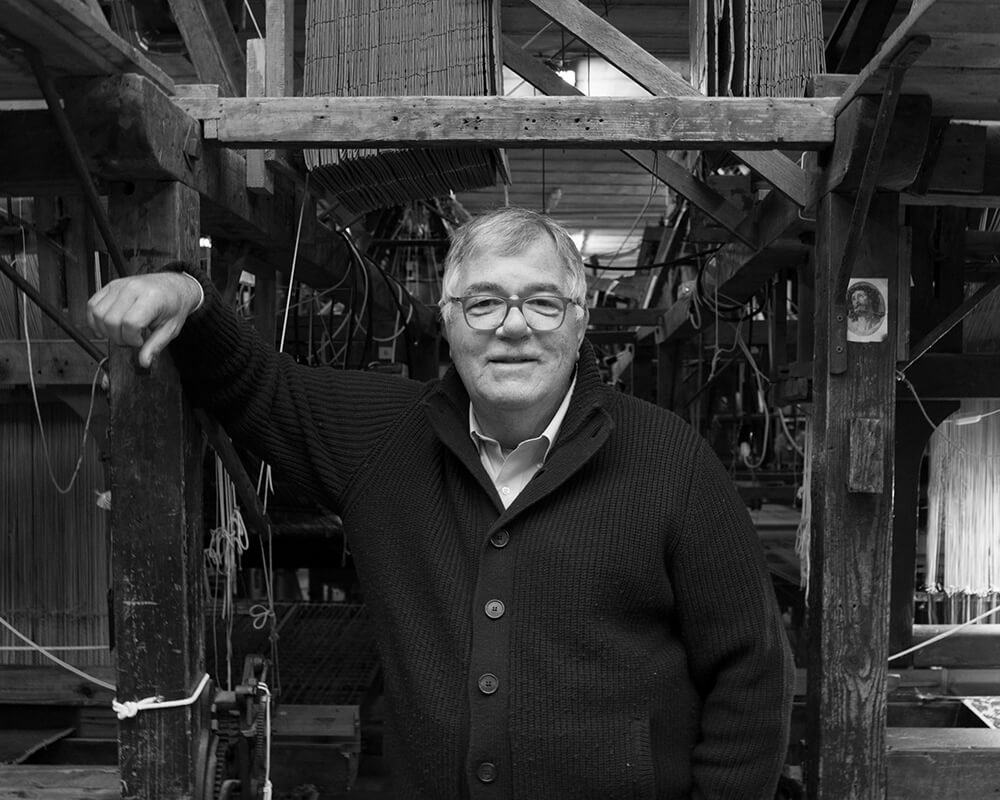

Tharawat Magazine met with Luigi’s great-grandson, Alberto Bevilacqua, Chief Executive Officer, to discuss the italian fabric industry, the importance of their traditional manufacturing methods and the pivotal role passion plays in a family-run business.

What was the business like when your great-grandfather first established it?

The company moved around several times before becoming established at our current site, where we’ve been operating since 1900. Before this location, we were at Palazzo Labia, on the other side of the canal, and near Piazza San Marco before that. At the beginning of the 1900s, there were almost 100 people working on three floors of weaving frames. We produced a considerable quantity of velvet and other fabrics intended for export to the United States, England and Scandinavia.

My grandmother was Swedish, which helped the company in Scandinavia. We were commissioned as the exclusive supplier for the Stockholm City Hall, one of Sweden’s most prominent buildings; the Noble Prize banquet is held there every year on the 10th of December. Our family worked closely with one of the greatest Swedish textile artists, Maja Sjöström, to produce fabrics for the City Hall. You can still go to the City Hall today and see our works.

Luigi Bevilacqua was also the official supplier of precious fabrics for the Pope and the Vatican until Pope Paul VI decided that the church should cut its expenditure on luxury goods.

Did you always want to be involved in weaving?

No, it was something that I fell into because of the nature of family businesses. The founder, my great-grandfather Luigi Bevilacqua, had many children and several brothers who have participated in the venture over the years. Like many other companies that have been in business for a very long time, ours has experienced both expansion and contraction. After pursuing other interests, I wanted to help the company following a period of serious decline in the textiles industry. I was 44, and my father, who was in charge of running the company, was also experiencing health issues. I felt it was important and necessary for me to contribute as much as I could.

The founder, my great-grandfather Luigi Bevilacqua, had many children and several brothers who have participated in the venture over the years. Like many other companies that have been in business for a very long time, ours has experienced both expansion and contraction.

You create original designs in addition to taking special orders. How exactly does that process work?

Our expertise means we work a lot in the heritage space. For example, we have three weavers who have been working hard over the last two years for a palace in Dresden, Germany. We are recreating the fabric that used to clad the walls of the palace in the 1700s and was lost during the war when the palace was razed to the ground. A fragment of the fabric was recovered and preserved, and that serves as our sole link with the past. We are using this as a reference to help us recreate 750 metres of splendour for the palace. Because of our niche expertise, we can help the palace maintain its heritage.

There are also items that only we can provide. For instance, we have been producing animalier velvets, fabrics with animal print, for over 50 years. Our customers, including those in the United States, rely on us to continue working on them.

We are broadening our portfolio along with our audience. Thanks to social media and mass media coverage, like television documentaries, word about our work has spread, and we are seeing more orders from diverse geographical locations and various segments of the market.

What is your perspective on new technology?

While society generally sees a certain tension between artisanal craftsmanship and technology, I see it as a functioning relationship. We use the Jacquard machine, named after its French inventor and developed over 200 years ago. It is an early computing machine that helps plot complex textile patterns using punch cards. Even though the textiles are created using traditional, manual methods, we have fully embraced technology here, and this is one of the few aspects of our weaving process that can be mechanised. However, it is people’s attitudes towards production that can be hard to navigate.

We find that in the high-speed economy of today, people are no longer willing to devote time to waiting. If a person would like to have a sofa, they are daunted by the idea of having to wait a year for the upholstery and the sofa to be made. The concept is hard to grapple with in our fast-moving society. Perhaps, to meet this challenge, we could produce smaller objects like accessories or artworks.

We use the Jacquard machine [to] plot complex textile patterns using punch cards. Even though the textiles are created using traditional, manual methods, we have fully embraced technology here, and this is one of the few aspects of our weaving process that can be mechanised. However, it is people’s attitudes towards production that can be hard to navigate.

Apart from using social media, are there other aspects of your company that you are looking to innovate?

We do want to pursue greater recognition through social and other media, and we intend to invest significantly in that area going forward. From a product standpoint, we’re looking into designing new fabrics and using fresh colour schemes that are better suited to modern homes and buildings. We’re also very interested in cultural and artistic initiatives that shine a light on what our city has to offer to the world with respect to artisanal products. The Internet has helped bring people, customers and industries closer together, but we believe everyone should experience Venice first-hand to truly appreciate its unique qualities.

What is the role of women in this industry?

Weaving has traditionally been done by women here. Men were involved as technicians, but weaving requires a lot of patience and precision – skills that are usually stronger in women compared to men. In the past, girls started working on the looms as apprentices when they were only twelve or thirteen years old because it would take them eight or even ten years to fully master the craft and become weavers.

Nowadays, apprenticeships cannot last that long, but it is still not an easy job to learn, and becoming a good weaver takes at least a couple of years. We offer internships to girls who graduated from art schools on a regular basis, and we see that the passion and the desire to learn are still there. Many of our weavers have worked here for more than fifty years and still visit us after retiring.

Weaving is not mere mechanical work. The weaver witnesses the entire transformation process, from raw materials to the fabric gradually taking shape. The job requires great patience, but seeing the final result come out of the loom with no defects also gives immense satisfaction.

How do you ensure your traditional production methods are maintained and passed along from generation to generation?

It is crucial that skills and knowledge are transferred within the family and within the workshop, especially as we are looking at a century’s worth of ideas and wisdom.

It is a great pain to witness the loss of such skills, as I did in places like France, where they no longer have experienced workers in traditional weaving methods. The subject is not included in the vocational school curriculum either. At Luigi Bevilacqua, almost all our weavers have been through art school, where they were exposed to the basic foundations in textiles and weaving. We work to ensure that our younger staff are mentored by the more experienced staff, some of whom have been with us for over 50 years. In this way, we retain the skills and knowledge in the family and in the company, and we continue to build on them in response to changing times. We need to stay passionate about our trade and encourage our staff to do the same.

We will need that passion everywhere. This loss of skill is a problem that is endemic in the entire industry. Our machines date back to the 1700s, so to say they have few readymade spare parts is an understatement. When our machines break down, or the parts get worn down, we need to go to other artisans for specially crafted components. They, too, would have had to master their skills from the generations before them.

[ms-protect-content id=”4069,4129″]

Is it important that a member of your family is always in the lead role of the company?

Again, it’s the passion and its transference that might ultimately benefit the most by having the family at the helm. An outsider may not feel the same way about our traditional manufacturing methods. All too often, profit and loss become all that managers are passionate about, while the benefits that can come from a longstanding, quality-driven brand are often overlooked.

How do you see the future of Bevilacqua company and the italian fabric industry?

Our first priority is to maintain what we currently have in terms of business and location. It may be more convenient to operate on the mainland, but we appreciate the charm that comes from manufacturing in Venice, and we believe our customers do too.

The sector itself is changing, and we have to be prepared to respond to that. Online shopping through platforms like Amazon offers consumers a lower price point on many products, but it creates a challenge for brands that operate primarily through boutiques or bricks-and-mortar locations. This trend has a significant impact on places like Venice where so much trade is dependent on tourism and personalised human experience.

We believe the intimacy of that in-person experience is worth fighting for. We do not advocate protectionism, but as a company, we want to work hard to present a compelling and attractive alternative to unfettered globalisation. We owe it to those in the past whose efforts and craftsmanship we have built on; we owe it to future generations, so that they too may enjoy the exquisite experience of Venetian craftsmanship.

[/ms-protect-content]