Tanihata is at the forefront of one of Japan’s oldest architectural traditions: Kumiko Ramma. The family company’s CEO, Tanihata Nobuo, is a traditionalist with a modern eye for business. The craftsmanship that defines Tanihata’s products has been passed down from generation to generation for centuries, but Nobuo is not averse to expanding on that base to take Kumiko Ramma to new heights.

Situated in a small workshop on the outskirts of Toyama city, the Tanihata Corporation continues to build upon and market the tradition of Kumiko Ramma through a combination of cutting-edge techniques and digital strategy.

At the same time, Tanihata remains true to its roots: Nobuo credits Japan’s traditional culture and spirituality as the driving force behind the company’s ethos. Their products are inextricably linked to these principles.

The eponymous company is no stranger to weathering adverse economic conditions. Tanihata began operating in 1959 and grew through the 1960s, a period when traditional Japanese practices were under threat from the trend towards globalisation. The fallback of the 1990s, which crippled Japan’s economy, saw Tanihata scale back its operations but continue on, only to thrive again in the 21st century.

Tanihata Nobuo’s entrepreneurial perseverance and enduring flexibility have seen the family business continuously evolve to meet the needs of its ever-changing consumer base. The company’s recent digitalisation of marketing and logistics has been a crucial factor in Tanihata’s sustained success.

Recently, Tharawat Magazine had the opportunity to speak with Tanihata Nobuo about how culture informs craftsmanship, the threat economic recession poses to traditional skills and Kumiko’s recent resurgence in the hands of the next generation.

What is the history of Kumiko Ramma?

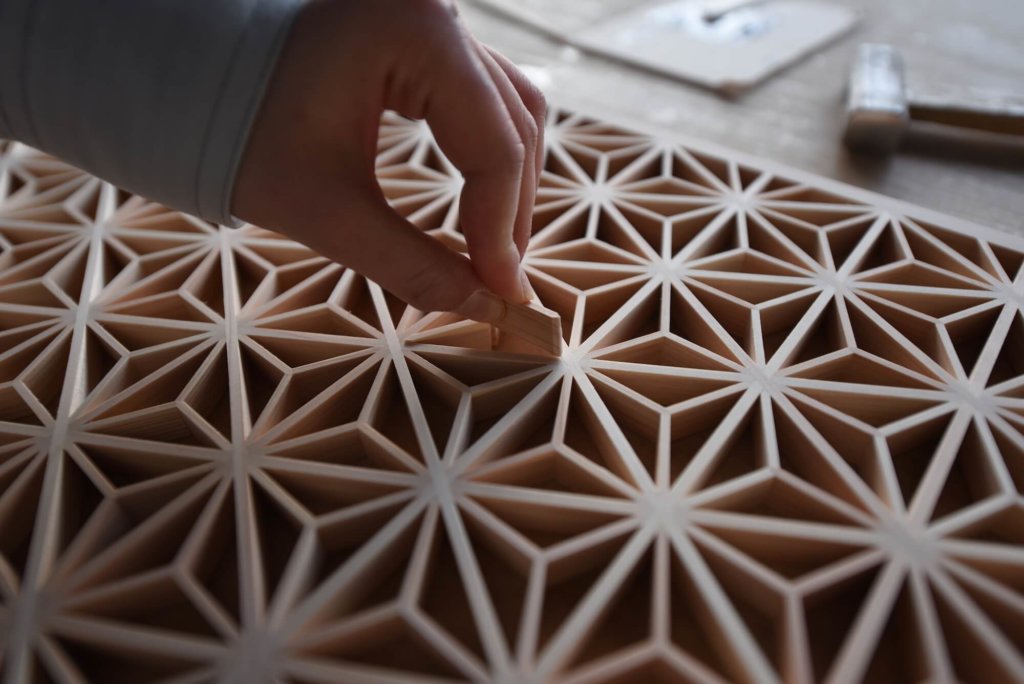

Kumiko is a woodworking technique that assembles latticework without the use of nails.

The origins of Kumiko can be found in the transmission of Buddhism-influenced architecture to Japan some 1,400 years ago during the Asuka period. At that time, carpenters were leaving China and the Korean Peninsula and coming to Japan. Not only did these carpenters bring an unprecedented level of skill, but they also brought innovation in the form of hatchets, chisels, augers, hammers and saws. These new technologies were a vast improvement on existing Japanese carpentry tools. From that tradition, it is thought that the basis of Kumiko’s techniques was born.

Ever since the Asuka period, Kumiko has enlivened Japan’s oldest structures. Its delicate latticework embellishment adorns the balustrades throughout Horyuji Temple, the world’s oldest wooden structure. The impact of its exquisite designs is unmistakable.

By the Heian Period (CE794 to CE1185), when the Heian Palace, the home of Japan’s nobility, was ornamented with sliding paper doors that contained Kumiko fixtures, the art had cemented its place in upper-class Japanese residential architecture.

Rooms with paper and wood partitions typify Japan’s traditional interior architectural style; they play an integral role in how space flows. The functional and ornate picturesque designs in residences are called Ramma – Kumiko is a style of Ramma.

Ramma was, until the Edo Period (CE1603 to CE1868), a privilege of the ruling class and wealthy merchants. The ornamentation of Japanese rooms spoke to the opulence of Japan’s most influential people.

Eventually, Ramma began to find its way into the average household. However, the economic fallback of the mid-1990s led to a decrease in the construction of traditional Japanese rooms. Our youth are increasingly moving into homes without fixtures containing Ramma. Even so, Tanihata continues to build on the legacy. Through the establishment of an industry for large-scale Kumiko panels, suitable for commercial spaces, Tanihata has redefined the concept of Ramma.

How did your father learn the craft?

My father Tanihata Toshio, the founder of our corporation, began learning Kumiko at the Industrial Crafts Research Institute in Saitama Prefecture. In 1969, he founded the Tanihata Kumiko shop in the city of Toyama.

We continue to build on his legacy through the transmission and refinement of his techniques as they apply to our product. Tanihata has been in operation for 60 years. Some of our seasoned employees have more than 50 years of experience. They play a vital role in handing down our time-honoured skills to the next generation.

My father Tanihata Toshio, the founder of our corporation, began learning Kumiko at the Industrial Crafts Research Institute in Saitama Prefecture. In 1969, he founded the Tanihata Kumiko shop in the city of Toyama. We continue to build on his legacy through the transmission and refinement of his techniques as they apply to our product.

How does Japanese culture contribute to the craft’s enduring popularity?

In Japan, there are currently more than 100,000 companies with a history of over 100 years. Even more remarkable are the seven companies that are now over 1,000 years old. Out of those 100,000 companies, 45,000 are tied to the manufacturing sector, a figure that demonstrates the long-standing tradition of craftsmanship in Japan.

Three essential elements exist at the core of Japanese craftsmanship: materials, tools and spirit. Those elements are inextricably linked to Kumiko Ramma.

Kumiko’s base materials are comprised of the lumber from Japanese cedar and cypress. At the very least, the trees are cultivated for 80 years to ensure the highest-quality product. The grain of the wood is fine and straight, without knots and uniform in colour.

Trees of that quality do not come from the mountains; they are grown on tree plantations. Specialised care is required to ensure a superlative end product. Kumiko craftspeople recognise this value and show their gratitude through the ethical harvest of trees.

Our perspective on tools is summarised by the famous architect of temples and shrines, Ogawa Mitsuo, who is quoted as saying, ‘I wish to do work that does not embarrass the tools.’ Japanese craftspeople take this as a mantra and treat their tools with the utmost care; we believe spirits reside in tools. When considering tools on an industrial scale, the blades and facilities required to process the trees are paramount. When it comes to the special treatment of tools, some Japanese artisans go so far as to deify their blades.

Spirit, the third tenet of Japanese craftsmanship, is harder to qualify. Japan’s total area makes up only 0.28 per cent of the world’s land mass but accounts for 11.9 per cent of the world’s total damage from natural disasters.

Exposure to calamities is part of Japan’s national identity. Since time immemorial, we have prayed to the mountain, the sea and the land that natural disasters do not occur. This worship takes place at some 77,000 temples and 88,000 shrines.

Our special treatment of materials and tools combined with our unique perspective on spirit informs every aspect of Kumiko Ramma.

Our special treatment of materials and tools combined with our unique perspective on spirit informs every aspect of Kumiko Ramma.

How do the skills associated with Kumiko Ramma pass from one generation to the next?

Initially, the techniques of Kumiko were only a small part of the ornamentation of wooden fixtures. Still, very few craftspeople rely on the technique of Kumiko alone; they make wooden fixtures and furniture while simultaneously transmitting the traditions of Kumiko.

On the outskirts of major cities like Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya and Shizuoka, production areas exist where sliding paper doors and other wooden fixtures are still made. In those areas, one can find the master craftsmen that possess the techniques of Kumiko. Generally, these skills are passed from father to son, thus preserving the trade throughout Japan.

Are young people interested in building and buying Kumiko Ramma?

Since the recession of the mid-1990s, very few young people live in traditional Japanese houses anymore. Several factors make traditional Japanese houses prohibitively expensive on a low budget. For example, tatami or paper sliding doors must be installed and maintained, which is costly.

At the same time, western-style household furniture became more popular because of its style and functionality.

The tough economic situation also impacted Japanese builders. For the most part, they shifted from a more expensive, traditional Japanese style to the Western style, which was cheaper to construct and easier to market.

Just over ten years ago, Kumiko sales decreased exponentially as a result of these changing market conditions. However, we breathed new life into the company by switching our focus from household to commercial production.

That said, Kumiko is seeing a resurgence. Japan’s youth have rekindled interest in the techniques of old. Traffic to our website and participation in our workshops have both increased. Perhaps most encouragingly, we have also seen a noticeable increase in young craftspeople taking up the trade.

Are you worried the traditional skills and techniques necessary to build Kumiko Ramma will be lost?

The Japanese lifestyle has significantly changed since I began working at Tanihata. We used to have regular business with nearly 300 shops that produced sliding paper doors and other fixtures, but as the number of houses that use these fixtures decreased, that figure is now less than half of what it used to be.

Even for us, 1996-2006 was exceptionally hard: we struggled to sell Kumiko and were very close to bankruptcy. Staff were relegated to simple tasks and, as a result, many resigned.

Digitalisation and a new digital strategy helped us turn the corner. As our clients increased thanks to these new initiatives, improvements in our design approach and the expansion of our market share resulted.

Our environment is continuously changing – fluctuation is the only constant. The retention of our time-honoured techniques is our focal point, so it’s imperative that we match our approach to sales and production to this changing environment. It is our duty to protect the craft of Kumiko.

What does the future of Tanihata look like?

I wish to share traditional Japanese culture through the spirit of Kumiko to the people of the world, as I believe it has a peaceful effect on the hearts of those that experience it.

Ideally, I want to internationalise Tanihata and Kumiko. However, I do not have aspirations for Tanihata to become a major corporation. I want to retain our current quality-to-output ratio.

In terms of family ownership, at 53 years old, I have three children. We have an open dialogue regarding the preservation of Kumiko Ramma and Tanihata, but I do not know what will become of it. That is a decision for my children to make.