Dr Jones is a professor of psychology at Missouri State University who specialises in industrial-organisational (I-O) psychology. His research in this area explores ethical decision-making and prejudice in personnel selection and development.

His fascination with the societal influence of nepotism, initially inspired by Adam Bellow’s In Praise of Nepotism, led Jones to conduct personnel testing to narrow the focus of I-O psychology in business. He makes a distinction between “family hiring” and “kin preference” and asserts the former, which considers the outcomes of these decisions, is a powerful tool for ensuring sustainability in business.

We spoke with Dr Jones about the stigma of nepotism, the potential to trivialise its societal benefits and whether or not family businesses can practice nepotism productively.

How do you define nepotism?

Nepotism is vaguely characterised by the hiring of relatives to benefit the family rather than the organisation. More specifically, nepotismp>

I suspect that satisfaction is lower where coercive nepotism> is concerned, and performance suffers despite the potential advantages of consistency. There is perhaps a trade-off: increased tenure at the cost of performance and satisfaction.

<p>There’s also some debate about whether the perception of nepotism leads to differences in satisfaction of the perceivers themselves. There’s evidence both ways, which may result from cultural differences as well as difficulties in defining the behaviour itself. an>

Decreased satisfaction in the workplace may simply be a product of “>nepotism’s stigma. There are examples of poor hiring decisions in all kinds of jobs, both family and non-family.

“…People in family firms align the interests of their core social group (family) with the interests of their workgroup, which results in increased commitment to the organisation.”

How can nepotism benefit a family business?

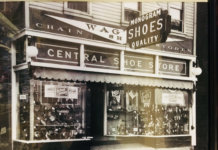

Here’s an example: throughout his adolescence, a young man works on the floor of his grandfather’s store, which specialises in Western wear. He goes to university, where he studies business, art and textiles. He returns to work in the family business and familiarises himself with all aspects of it while at the same time getting his Master’s in Business Administration.

Because of his love for the business, he is more qualified than any other candidate for an executive position in the company. Open communication proves that there are equitable processes in place, doing away with the stigma of nepotism.

In productive examples such as this one, processes are set into place and visible. Decision-making is above board, takes the interests of all stakeholders into account and typically arrives at a favourable outcome. It is not always perfect, but it is equitable. >

Our fundamental commitment to our family is often more important than our commitment to our occupation. How these commitments influence each other is something that deserves further examination.</p>

The consistent hypothesis here is that people in family firms align the interests of their core social group (family) with the interests of their workgroup, which results in increased commitment to the organisation.

<p>There i</ps also some evidence suggesting that nepotismn> is essential for people from disadvantaged groups to make a consistent living in a society that’s hostile toward their group. Those familial ties help individuals who are otherwise underprivileged and have the potential to generate long-term benefits that get people out of poverty.

What strategies are most effective in the prevention of nepotism?

Systematic hiring procedures that are common in larger organisations include abilities tests, personality inventories, structured interviews and work samples. In fact, I’ve helped numerous organisations to implement these procedures, which rely heavily on actuarial statistical analyses to show that they are related to important work outcomes. They’ve been tested extensively in court, in the US and elsewhere, with very positive results as a rule.

<p< span=””>>Other organisations have anti-sm”>nepotismb>

Until I-O psychologists took a look at this problem, there was little evidence to work from, despite several court cases that dismantled the use of anti-sm”>nepotism policies. As a result, we’ve begun to distinguish ‘family hiring’ from ‘kin preference’ in hiring. This distinction considers the outcomes of these decisions on the business, and only the latter is negative. [ms-protect-content id=”4069,4129″] Evidence suggests that efforts towards corporate social responsibility are generally window dressing. Attempts to eschew nepotistic practices are more for show and to enhance profit opportunities than they are indicative of actual changes in the ways that organisations do business. Family businesses are more interested in sustainability. It’s not coincidental that Ford, the American car firm that needed the least help in the bailout and was the first to adopt hybrid cars, is a family company. The long-term perspective that typifies family firms may lead them to take initiative before other companies in their sector when it comes to sustainability. <p>We are inherently social animals, and for the most part, our core bonding occurs primarily at childbirth and in infancy. How we manage relationships is one of the critical issues surrounding productive nepotism>.Are family businesses currently trying to disassociate themselves from the practice?

Is there a way to practice nepotism constructively?

The way an organisation goes about hiring people, if well considered and consistent with the organisation’s culture, deals to some extent with those relationships. Productive nepotism must remain consistent with the expectations of external stakeholders such as the law, for example. If it meets these expectations, family hiring could be an incredibly powerful force for good.

[/ms-protect-content]

</p<>