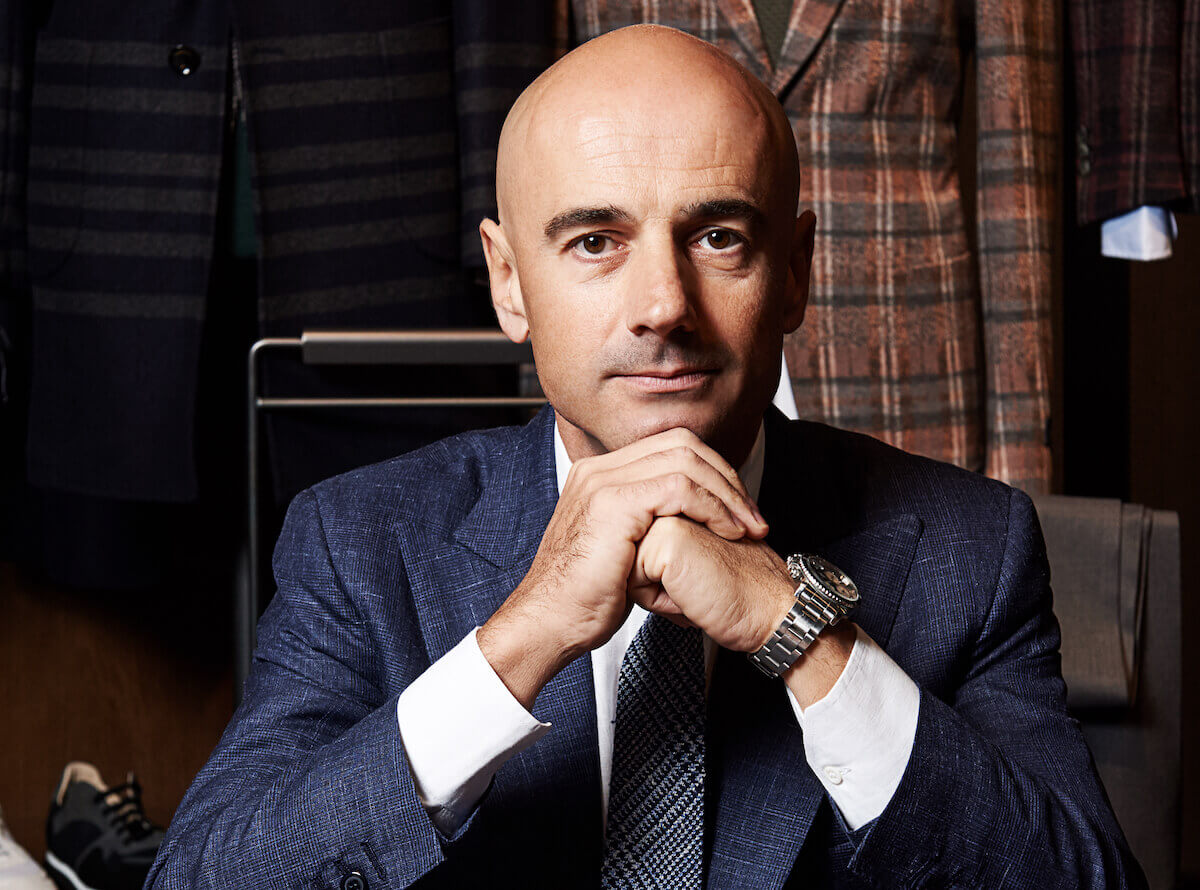

Interview with Alessandro Barberis Canonico, CEO, Vitale Barberis Canonico, Italy

Whoever suggested the secret of success is doing one thing and doing it well must have had Vitale Barberis Canonico in mind. For more than 350 years, this Italian family has been producing some of the most exquisite wool textiles in the world. Walk into any of the finest men’s clothing shops in the world from A. Caraceni to Panico, to the tailors of Savile Row, and you’ll find woollen material produced by Vitale Barberis Canonico.

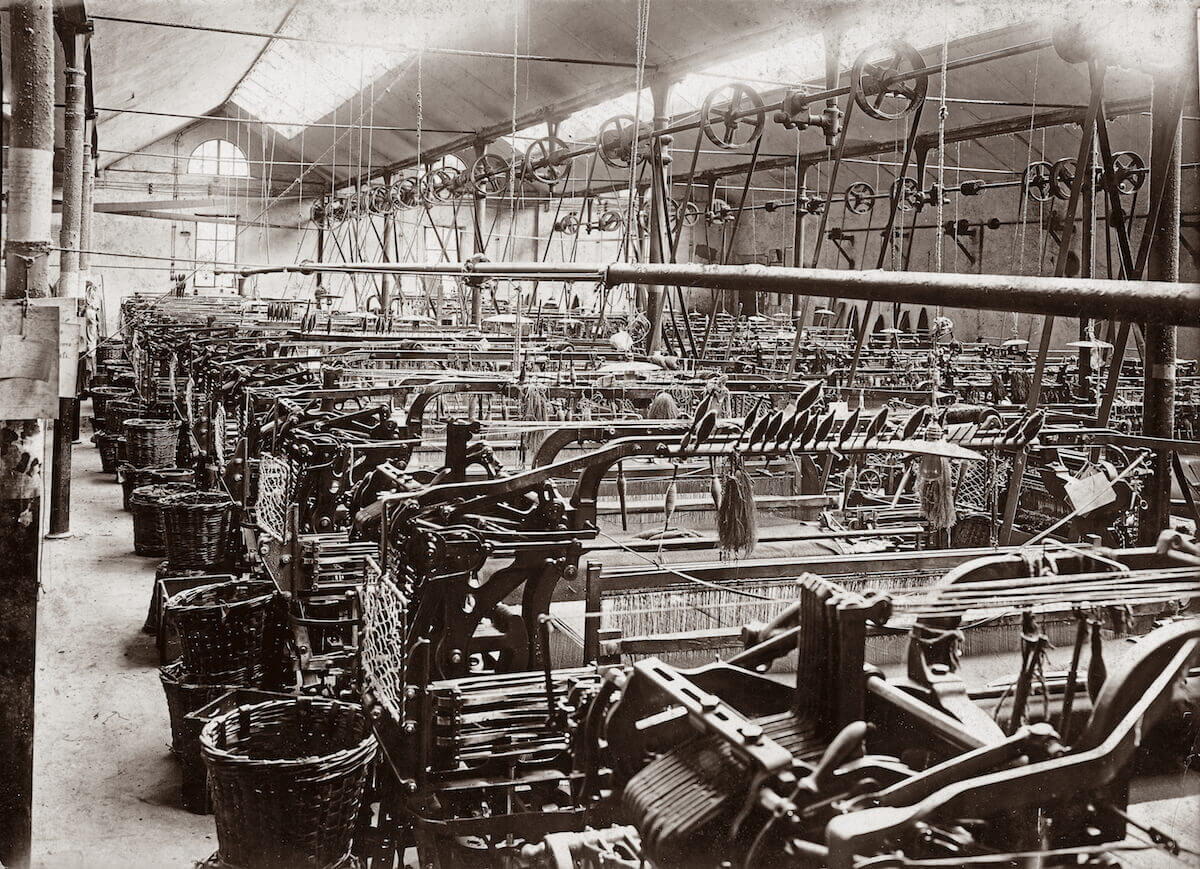

The first documentation of the family’s wool-producing activities dates all the way back to 1663 when operations began in Pratrivero, in the Biellese Prealps, Italy. The region became known as the heart of textile-production, where the best waters flew for the processing of high-quality wools. The company officially took the name Vitale Barberis Canonico in 1936.

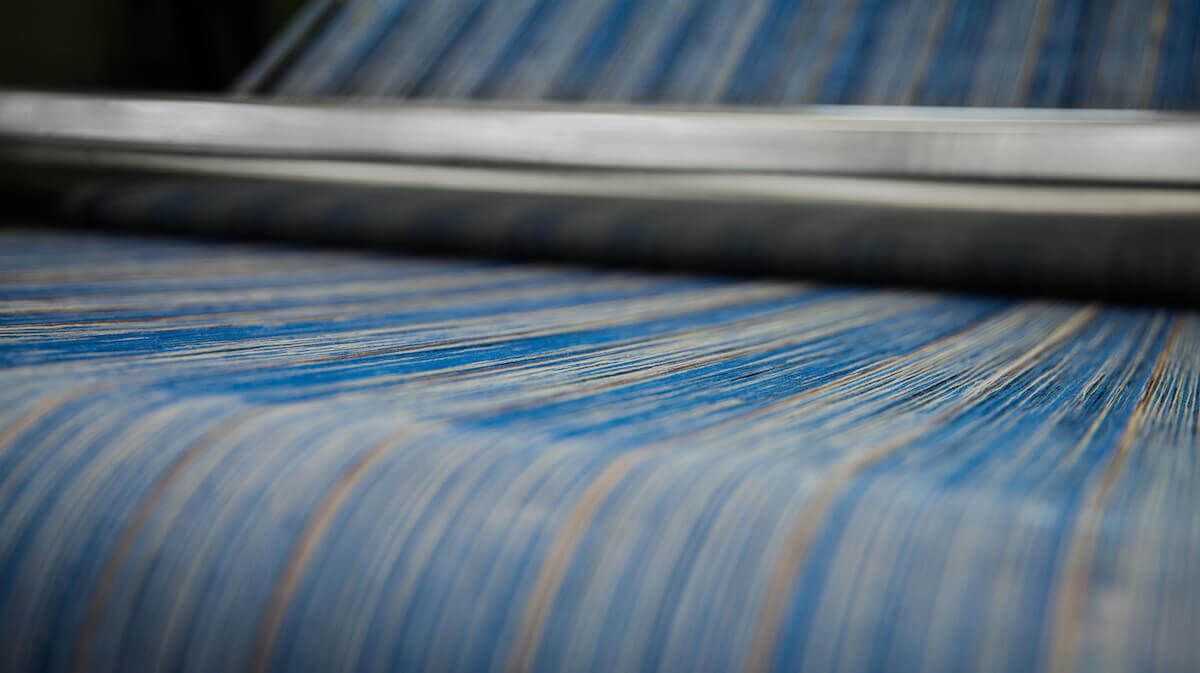

Despite the recent economic downturns, business at the family plant has never been better. Production has increased this decade from 6 million m in 2010 to more than 10 million m in 2016. Each year the plant processes four million kg of greasy wool into yarn. In turn, that yarn is woven into material for suits which will then be exported to more than 90 countries around the world.

One of the keys to the company’s continued success in this advanced technological age is their seemingly paradoxical marriage of tradition with innovation. When current CEO Alessandro Barberis Canonico first joined the family business in the late 1990’s, he was tasked with helping to implement a new production system which remains in place to this day including automation and robotics. By introducing automation into the process, Barberis Canonico has been able to maintain high standards while enjoying efficiencies in manpower, water, and power consumption.

Tharawat Magazine had the opportunity to tour the production facility and speak with Alessandro Barberis Canonico about his family legacy, the challenges in supplying the modern fashion industry and what it takes to merge an old industry with new technology successfully.

How far back can you trace your family’s roots in this industry?

We know it goes back at least to 1663 because we once found a tax bill for their business that was sewing fabric. But I’m fairly certain it goes back to well before 1663 because we found some clues of fabric producing activities.

Have you been told the tales of what your grandfather and those who came before him did in the business?

My great, great grandfather ran the business in the late 1800’s. At that time, we managed only the last part of the cycle, so not the spinning but the weaving, warping and finishing. My great, great grandfather had ten children, and he divided the business into five pieces, giving each part to a couple of his children. My grandfather together with his brother built this factory, and they focused on the warping, weaving, and finishing processes. In 1936, there was a family fight, and they stopped the production and divided the business. My grandfather split from his brother, and he built his own company which was tiny compared to the family’s previous operations. When my father was a manager at the factory in the 1970s, he developed the spinning side. Then in 2001, we added the dyeing side. We expanded into the entire production cycle from the 1970’s to the early 2000’s. This fully automated plant we’re in right now was built in the 2000s.

What are the central values of your family that have made you successful in your industry generation after generation?

I can’t speak for those in the past, but I can tell you what the last three generations believed. It’s all about the values that your family bestows upon you. First, it’s not just the family but also the workers who live these values every day: Clarity, honesty, the ability to work hard, and the willingness to suffer to reach your goals. You sometimes must sacrifice personal convenience because you’re working towards completing a big project. It’s important to us to always connect with everyone on the front lines of the operations. Ask how things are going, find out everything there is to know in each department. And then, look to hire the best people. Find people who are better and smarter than you. And you’re continuously investing in them, sending them to courses, sending them around the world to see new technologies.

I also think after all these years this industry is in the DNA of everyone around here. A lot of these people come from families that have worked in the various plants around this area for two or three generations. Every five years we open up the facilities to the families of our employees so they can show them where they work and what they do.

The technology may have changed, but the essence of what you do hasn’t in 350 years. You produce wool material for the finest tailors and brands around the world. In this new age of instant gratification and online shopping, why do you believe this traditional approach still appeals to people?

There’s nothing out there that can equal a tailored suit made from some of the finest wool in the world. And you can’t find the shops that will do this just anywhere. They’re in Italy, London, and Paris, but not in the United States or China. But here, people will go to the shops, choose their fabric, and then go to the tailor and have the suit made. This is the traditional way.

Today you can go on websites or other places where you can find some but not all of the fabrics and ask them to create your suit. But you can’t find out what you need to know about the fabric online. What it feels like to the touch, how it looks in a certain light. You can’t discuss the styles, or get help matching the colour with a shirt and tie. So even if you go on the website and do sort of the same thing, in the end, it’s still going to be an industrial suit and not a tailored suit.

You are in a very old industry, but you have found a way to implement the latest technology. How important is automation in what you can do and how have you been able to marry these seemingly competing concepts of tradition and innovation?

Often people only view automation through the lens of being a means to drive down the cost of labour. But keep in mind that every shipment of wool is completely different, so to get it to come out as a standardised product of a certain quality, automation is critical. It allows you to adjust the machine better, you can ensure it runs properly to the correct specifications and maximum quality.

Case in point – every day we dye eight tons of material automatically, without the involvement of people. This does two things for us: First, our cost of labour is low and secondly, the standardisation ensures a high-quality outcome every time. The system is very smart, if a recipe comes through that doesn’t seem to match the parameters, it will simply skip to the next job. We have a very narrow margin that we must hit to get the colour exactly right, and we are successful more than 99% of the time. It took us five years to perfect the system and get it working at the level it does today.

How did you take the first steps towards innovation?

Because I studied engineering at the University, my first job was developing the new production system. I started by assisting the ETC manager with the start of the new system in 1997. At that time, that kind of wide-ranging network system was a novelty. Nobody had seen a system that combines production and commercial outputs with all the other departments all linked together. And right away it started to yield positive results. When I took this job, the lead time was four or five months. At the end of three years, that was reduced to two and a half or three months at the most.

Did you always know you would be involved in the family business?

From what they say, I think I was born for the business. When I was little, maybe five years old, I remember my father would take me to the factory. He’d walk around the various departments, and I was by his side the whole time. Later, I would work in the factory during the summer. My mother would get upset because whenever we would have a family dinner, we would never talk about holidays or things like that, my father would always talk about the latest developments in the system and how the machines were running. The reason why I wanted to study engineering and nothing else was to be part of the family business. It’s funny to think of that system that I set up at the beginning of my time at the factory is still the one operating today.

Today businesses must be very conscious of their environmental footprint, especially with an operation as large as yours. How have you dealt with this issue as you’ve modernised your system?

Our goal is to treat the environment the best possible way we can so we have a complete water system outside the mill and 25% of the water is reused. Our target for next year is to make it 50%.

How long does the process take from the very beginning to shipping the finished materials to your clients?

It takes us two and a half months to make the yarn. From the moment we obtain the yarn and dye it, it takes about a month. Then about another two weeks to do the spinning, warping and weaving. And then finishing it is a complex process and that takes us another month.

Is the demand constant year-round or is it seasonal?

Currently, we are at the height of the seasonal demand. We have to be quick to meet the demand. Right now we are producing the orders for next summer. The last deliveries will go out at the end of the year then the garment manufacturers will receive it between January and February. The shops will then receive the finished product in April and May. The Americans, for example, want their quantities now in the early autumn. They will make the garments near November, and December. It wasn’t long ago when we only had two seasons, but now we have some clients that have six seasons. Other even have twelve seasons because they want to renovate the shop every month with new fabrics, styles, designs, suits, and shapes.

What are some of the more memorable trends you’ve seen throughout the years?

The most prominent trends we’ve seen were in the 80s and 90s with strong stripes. Today those styles are considered classic. In the 90’s, the primary colour was grey. Today it’s blue, and in the last three or four years, it was trending towards bright blue. The fashion today involves smooth suits with strong material for the jackets. Because the current trend is not to wear ties with the jackets, you need something in the jacket that will match with the shirt. I believe a gentleman needs a special suit for every occasion; so I have a significant quantity of suits and jackets and ties!

To not just survive but to thrive as your family business has for 350 years is no small feat. You’ve weathered four different industrial revolutions. How have you been able to survive not just the latest disruptions, but also all those that came before it?

That’s right, four different industrial revolutions and the first one saw my great grandfather dealing with the move towards industrialisation. He decided to move from high-quality to mid-level-quality when the primary automatic looms came in. Then the other change was in 1970 when the real atomisation came. Italy was well positioned because the wages were quite low so they could reinvest a lot. The world was growing so I think the trend of internationalisation helped it. We survived because we grew around the world. We could compete not only in the high-end market but also add mid-level range in the retail sector. Because the world is growing, not only was the suit an important item for the luxury market, but it was also important for the general business market. Within the last ten years the Chinese market, Japanese market, and some of the American market and grew significantly. That gave us the capability to go from 6,000,000 m a year to 10,000,000 m.

What is your biggest wish for your family business right now?

I want to hand over the business to the next generation in the best possible shape. I want to grow the business, contribute to a better industry, with new clients with new fabrics, and a lot of innovation for the next generation. The last generation did that for us, so now we need to do that for our children too. Someone once asked me what my biggest problem is. I answered that I have more ideas than I have time to realise them. So hopefully whatever I can’t do in my lifetime, the next generation will be able to carry out.