By identifying a niche in the hypercompetitive Indian market and maintaining a strategy of continuous product development, Symphony revolutionised the air coolers category.

After making a public offering in the early 1990s, founder Achal Bakeri acted on the advice of his investors to rapidly expand Symphony’s product line. Ostensibly, widening the scope of their catalogue would enable them to access an increasingly broad customer base.

Instead, it drained the company’s reserves. Rather than declaring bankruptcy and walking away, Achal Bakeri remained resolute, confident that a return to Symphony’s roots was the only way forward.

Bakeri scaled Symphony’s focus back to the appliance that defined their initial success: air coolers. Differentiated from air conditioners by the use of evaporative cooling rather than harmful chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), air coolers provide environmentally friendly relief to atmospheric heat. After stemming losses and returning to profitability, Symphony embarked on a series of bold acquisitions to internationalise and began marketing air coolers globally.

Today, Symphony is the world’s leading manufacturer of air coolers. In addition to its operations in India, Symphony owns three subsidiaries in Mexico, USA, China and Australia.

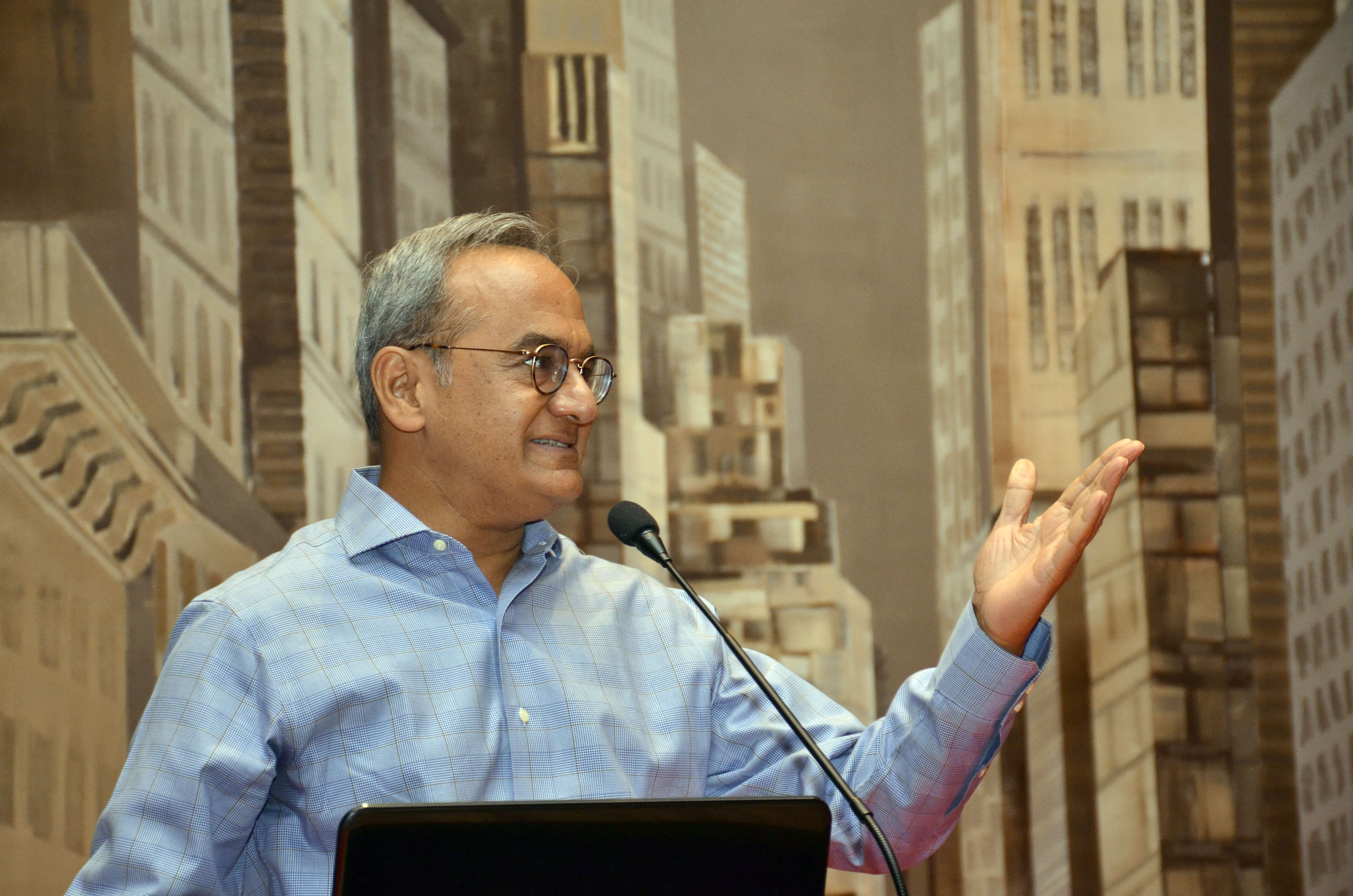

Tharawat Magazine had the opportunity to speak with Achal Bakeri to discuss the early days of Symphony, the company’s rebound from a period of precipitous decline and the global business community’s changing perceptions of India.

Real estate is your family’s predominant business concern. What inspired you to change direction and enter the world of air cooling?

I joined the family business in 1986. After 28 years, it was already well established, and I felt I had very little value to add to the organisation.

With an eye towards entrepreneurship, I noticed an opportunity in our own home: some rooms could only be made comfortable using an air cooler. Of course, at that time, functional air coolers were available in India, but they were ugly and disruptively noisy.

My father said, ‘Why can’t you make a better air cooler?’ I founded Symphony in early 1988, introducing a prototype of our current model to the local market.

The response exceeded my expectations, giving me the confidence to expand. Over the next few years, I scaled the business rapidly. By 1990, we had established distribution all over India.

How did making a public offering change the company?

In 1995, we went for an IPO and were listed on the Indian stock exchange. Our investors perceived weakness in Symphony’s business model: a seasonal-product company in a single category. They believed we had the brand and manufacturing capacity to gain traction across a wide range of appliance categories, which would allow us to sell products all-year round instead of only in the summer.

At their behest, we developed counter-seasonal and counter-cyclical products, including water and room heaters. The market was already saturated with these appliances, but we felt there was significant room to add value through innovation.

Despite our efforts, diversification was a consummate failure. We incurred heavy losses and, in the span of six years, exhausted our capital. Symphony was bankrupt.

Did you consider folding at that point?

No, not even once. I had the family business to fall back on but was unwilling to give up on the company I’d founded. Symphony had become part of my identity.

Stemming losses was our priority. We exhausted our inventory and ceased manufacturing operations in the other categories. In time, we exited and refocused on the business of air cooling.

In diverting our attention to diversification, we had stopped innovating. Although air coolers were still profitable, the business had stagnated. To rectify the situation, we developed new air-cooling products and moved to distribute these products internationally.

Was it difficult to make the shift away from diversification and back into a niche market?

At its core, Symphony has always been a product innovation company. In pursuit of diversification, we directed our research and development towards a wide range of products. To change, we simply had to redirect our focus – the fundamentals remained constant.

I’ll add that this process happened incrementally over an extended period. Retrospectively, the transition may appear sudden, but in reality, it occurred naturally and progressively.

How has the transformation of India’s economy informed Symphony’s strategy to internationalise?

Through the 20th century, India was viewed as a categorically poor country. Around the year 2000, however, perceptions changed. India became a smart nation, with an abundance of engineers, programmers and IT technicians.

The Indian economy has matured at an exceptional pace; Indian companies are now some of the world’s most influential. Six months ago, we acquired a company in Australia. This was a first for us: owning a subsidiary in the West. We were apprehensive about how Australian staff would respond to Indian ownership.

Our unease was unwarranted, however. The transition was remarkably smooth. In fact, most of their employees believe that, over the long term, the majority of companies worldwide will be acquired by Chinese or Indian groups. Our immense populations fuel GDP growth and, in many ways, provide a competitive edge.

When you make an international acquisition, do you attempt to instil Symphony’s culture or do you let that subsidiary’s culture take shape naturally?

We leave our subsidiary’s cultures undisturbed, allowing internal management structures to continue in the same fashion. Except for one Chinese company, where legal restrictions required us to do so, we don’t even change the names of the firms we buy out.

Our philosophy is: we buy these companies because they are thriving. Why disrupt the elements which led to their success?

Instead, we impart our financial awareness around growth, cost-mindfulness, margins and bottom lines – universal concerns which sustainable businesses require regardless of culture.

We leave our subsidiary’s cultures undisturbed, allowing internal management structures to continue in the same fashion. Our philosophy is: we buy these companies because they are thriving. Why disrupt the elements which led to their success?

[ms-protect-content id=”4069,4129″]

How do you approach the issue of environmental sustainability when it comes to Symphony and its subsidiaries?

The very nature of our product makes it an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional air conditioning. Air coolers consume no freon, no CFCs and less than a fifth of the energy comparatively. Low wattage is perhaps our product’s most compelling feature when it comes to markets like India.

How did your background in family business contribute to your success as an entrepreneur?

I credit the entirety of my achievements to my background in family business. I grew up in an entrepreneurial culture. My father, uncles and even my grandmother were supportive of and encouraged industry, which fueled the drive to succeed in myself, my cousins and my siblings. Also, the ability to leverage my father’s extensive network opened doors for me through the early years.

I credit the entirety of my achievements to my background in family business. I grew up in an entrepreneurial culture. My father, uncles and even my grandmother were supportive of and encouraged industry, which fueled the drive to succeed in myself, my cousins and my siblings.

What does the future of Symphony look like from a managerial perspective?

I have two daughters; both are grown and recently married. One is a doctor and lives in the US, so she’s unlikely to come back to the family business.

My eldest is in Mumbai and sits on the board of the company but is not directly involved in operations. However, she’s spent considerable time in the business over the years and has worked in every department.

That said, we are not a typical family business in terms of concentrated ownership. Although my family owns 75 per cent of the equity, more than 16,000 investors, individual and institutional, own the remaining balance. Symphony is under my leadership as the CEO and founder at the moment, but that’s where it ends.

[/ms-protect-content]